Spain accused of 'scaring off and intimidating' short-sellers in Grifols case

For decades, Grifols grew rich from an empire built on blood. Founded by a plucky scientist and his two sons in the years after the Spanish Civil War, the company made a series of breakthroughs that revolutionised the science of transfusion – and hit upon a lucrative new line of business. By tapping the veins of cash-hungry blood donors, separating the plasma and selling it on, they built a business that reached a valuation of almost €20bn.

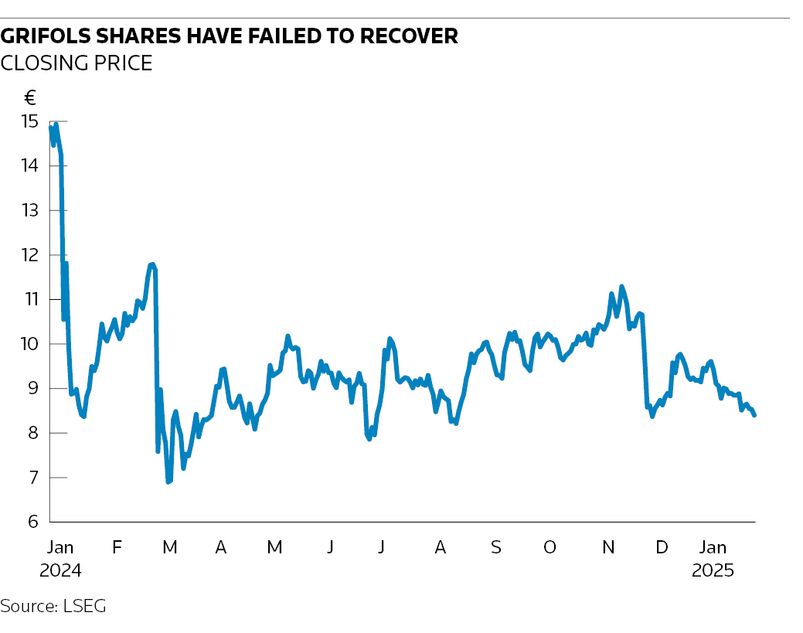

Until one day, a year ago, when the Grifols share price suddenly haemorrhaged. Gotham City Research, a New York-based activist short-seller, published a report alleging that Grifols had deceived investors and obscured its true level of indebtedness. The company’s shares opened 43% lower on January 9 2024, wiping billions off its market value. “Nothing comparable to this has ever happened in the history of the Spanish stock market,” Grifols' lawyers said later.

The CNMV, which regulates the Spanish stock market, immediately launched an investigation and in March published a report identifying “significant” deficiencies in Grifols’ reporting that “hindered the ability of investors to adequately understand the financial situation”. Following an eight-month investigation into the matter, in September the CNMV published two reports – one examining the role of Gotham and the other probing the accuracy of Grifols’ financial reporting.

The reports concluded that both Gotham and Grifols should be sanctioned for potentially “very serious” breaches of market abuse law. Days later, the CNMV referred the case to the public prosecutor. But it only referred Gotham for potential prosecution. That decision sparked disbelief among the small industry of researchers who seek to publicise alleged company wrong-doing and aim to profit by short-selling those companies' shares. They fear that regulators once again have activist short-sellers in their crosshairs – after campaigns to discredit their work exposing issues at German payments company Wirecard, French retailer Casino, Chinese property company Evergrande and South African bank Capitec (among many others).

“This is all about scaring off and intimidating short-sellers,” said Fraser Perring, the founder of Viceroy Research, who was pursued by the German regulator for highlighting fraud at Wirecard. “We saw that in Hong Kong, where Citron Research was forced to leave after being fined for Evergrande. They tried to fine us in South Africa for Capitec. It’s clearly sending a message. And I would encourage people to ask: if the response is this, what else is there under the hood?”

Shock decision

The Spanish High Court has since taken on the case, with the assigned judge saying that enough evidence has been found against Gotham to merit an investigation into the possible violation of market and consumer protection laws. The short-seller has rejected the charges calling the investigation “perfunctory” and saying it received just a single two-page letter from the CNMV.

Gotham alleges that the charges against it could be politically driven. Grifols is Spain’s most successful biotech. Its owners are well connected. In a deposition filed in a lawsuit in New York, where Grifols is seeking to sue Gotham for damages, Cyrus de Weck – one of the defendants – accused the CNMV of failing to engage with the short-seller or its lawyers. He alleges they didn’t hear from the CNMV for months – and that the public prosecutor failed to respond to requests to meet. De Weck is a founder of General Industrial Partners, a hedge fund affiliate of Gotham. Gotham declined to comment.

“The CNMV and public prosecutor also refuse to provide us with key documents they claim served as part of their basis for their recommendation for prosecution,” he said in a signed affidavit. “Likely it is all based on Grifols’ unsupported, unvetted and as yet uncontested accusations. Grifols is family-owned, and the Grifols family is widely known to be influential in Catalonian politics. The prime minister of Spain depends on support from the Catalonian government to maintain a majority in Spanish parliament.”

Like in many other major countries, the head of the Spanish stock market regulator is a political appointment – although most of its staff are independent, career-long public servants. According to Elvira Rodriguez, who headed the CNMV a decade ago and who had her own run-in with Gotham when it exposed falsified accounts at Spanish wifi provider Let’s Gowex, which later filed for bankruptcy, such cases can be highly embarrassing – but need to be handled completely apolitically.

“On the one hand, it obviously doesn’t look good for the CNMV when a short-seller comes out and identifies things that the regulator might have missed,” she said. Indeed, some of the accounting methods used by Grifols were investigated – and cleared – by the CNMV in 2019. “But what is quite clear is that you can’t respond by attacking the way that short-sellers work because it’s completely legal. What has to be established is if there is any wrongdoing.”

When asked about its handling of the case, the CNMV said: "During our investigations, we follow several proceedings and use different tools. However, supervisory actions taken on our side are subject to professional secrecy." It said it referred Gotham to the public prosecutor after finding "indications of possible market manipulation". It didn't comment on the potentially "very serious" infringements committed by Grifols – but said that sanctioning proceedings against the company are ongoing and will be communicated publicly in due course.

Grifols did not comment when asked about the CNMV's decisions – or about the allegations of political influence. When asked why it was suing privately in the US but not in Spain, it said: "Our legal complaint against Gotham and GIP, filed in the US federal court in January 2024 and under civil law, reflects the appropriate jurisdiction and venue based on defendants’ operations and is separate from the criminal case that the Spanish High Court chose to initiate."

"Market abuse"

The criminal case against Gotham in Spain appears to revolve around whether the short-seller breached European laws on market abuse that were introduced in 2014. The judge overseeing the case has said he is investigating the potential “dissemination of news or rumours ... that could contain totally or partly false information” covered by the market abuse laws. But lawyers say the new laws are problematic – in part because of the vague way in which they are written.

“The main rules that apply to short-sellers – and especially the market manipulation rules – are harmonised at the European level, but enforcement varies considerably,” said Paul Oudin, a law lecturer at the University of Oxford, who has advised in various cases involving short-sellers. “The rules are very, very broad and not very clear, and so there is a lot of room for interpretation, which means that from one jurisdiction to the other you can have very different views.

“Pretty much anything that pushes prices in a direction that is not reflective of the company's fundamental value can be considered market manipulation,” said Oudin, adding that while regulators might flag potential abuses, prosecuting them is a different matter. “The legislation is very broad – there is no clear list of what specifically market manipulation is. Regulators have considerable legal discretion. Unlike in a criminal case, they don’t usually have to prove intent.”

Lawyers for Grifols are certainly claiming criminal intent. In the New York case, they have labelled Gotham “fraudsters and criminals who authored, published and disseminated a knowingly false report to create a panic-driven, artificial selloff of the company’s stock”. For its part, Gotham has criticised the New York case as “costly and punitive” – designed to stifle freedom of speech. It says its analysis was based on public information and that its short positions were fully declared.

Short-seller Perring said the Spanish reaction reflects a wider backlash against such exposures. “Companies are using political clout – or the threat of political clout – to justify wrongdoing,” he said. “You're seeing regulators react by saying that it’s market manipulation, even when the facts are correct. It’s bullshit, and my concern is that you're getting this more nationalist agenda, of 'how dare you come to our backyard and point out issues'.”

Treading water

One complication in the “artificial selloff” argument is Grifols' share price, which still trades 20% below where it closed on the day Gotham published its first report. The fact that the share price has continued to slide – even after the CNMV wrapped up its investigations and after Grifols restated its financial reports to correct deficiencies – indicate the market has ongoing concerns about the way Grifols is run, because the fall in the company’s share price has not been corrected.

“Short-sellers are just investors, and the fact that they short a company when they think that is the right view is a good thing,” said Oudin, who added that – to be market manipulation – short-sellers would need to push prices in a direction that does not reflect the company’s fundamental value. “It's not a good thing because they're good people, or because they're making a lot of profit. It's a good thing because it contributes to the efficiency of financial markets.”

Indeed, many of Gotham’s allegations were corroborated by the CNMV’s investigation. While the Spanish regulator disagreed with some of the conclusions made by the short-seller – particularly around Grifols' debt levels – it also said that Grifols “omitted certain information, or included inaccurate data” and has forced it to restate financial statements. It has also asked the company to provide investors with additional information about how it calculates debt levels.

Two weeks ago, Mason Capital Management – one of Grifols’ largest shareholders – sent an open letter to Grifols' board highlighting “numerous corporate governance failures” that have resulted in the depressed share price, urging the company to take immediate remedial action. It highlighted a €7bn offer from private equity company Brookfield Asset Management that “dramatically undervalues the company”. Brookfield eventually walked away from the deal.

Grifols has managed to weather the storm in public markets – thanks to some help from private investors. When Gotham published its first report, the biotech was facing some big debt hurdles – the maturity of €1.9bn of bonds and a US$1bn revolving credit facility, both in 2025. But the company has signed two private placement bond deals, raising €2.3bn of liquidity – albeit at much higher interest rates. It has also increased and rolled over its RCF to 2027.

Turning point?

While the court cases now playing out in Madrid and New York will be critical to restoring investors’ confidence in Grifols, other short-sellers believe the decisions could mark a turning point. When German and French regulators were forced to backtrack on action against short-sellers after their reports on Wirecard and Casino proved to be accurate, they sensed a thaw. But the new Spanish case could set a dangerous precedent.

The industry is already reeling from the costs – and risks – of doing business. Activist short-seller Nathan Anderson announced plans two weeks ago to close his firm Hindenburg Research, adding that the job was “rather intense, and at times, all-encompassing”. As well as legal and regulatory attacks, short-sellers have also been the victims of surveillance, character assassinations and other intimidation techniques.

If the European landscape becomes more difficult in which to operate, market transparency could take a huge knock. “Most analysts – and I say most, not all – are blinkered because of the question of fees, because they want fees in the future,” said Perring. “And very few have actually done the deep dives that we do. If anything, short-sellers force companies to be as transparent as possible. People should absolutely be paying more attention to how companies conduct themselves.”