2009 was a remarkable year. Just months after global banking had been saved from an extinction-level event (leaving some notable roadkill behind), the industry was suddenly making out like bandits – a description some would have thought appropriate.

It was a year of record fixed-income, currency and commodity trading revenues as spreads widened and firms with a strong trading DNA had blowout years. The strong market rally from March onwards made investment banks bullish about a recovery in dealmaking.

Will 2024 mark the beginning of a rebound for investment banks? Or, like 2009, will it prove to be another false dawn?

There’s no question that US investment banks had a strong 2024 after fourth-quarter revenues and profits came in well ahead of estimates. The expectation that Donald Trump's new administration will herald a pro-business era, complete with looser banking regulations, has undoubtedly released animal spirits.

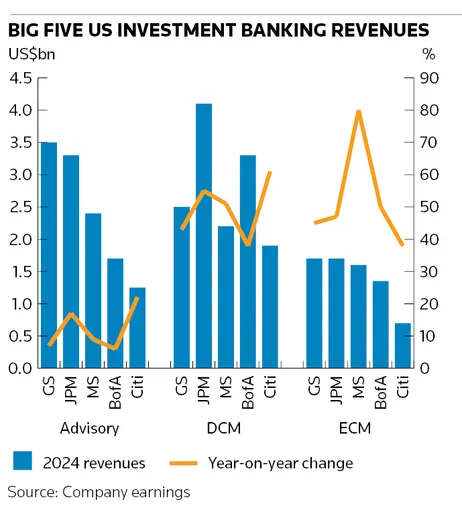

Following a quiet 2023, investment banking registered a striking year-on-year performance, with the five major US banks growing deal fees by 34% on average. DCM remained the engine room, with revenues increasing about 50% to US$14bn. JP Morgan continued to be head and shoulders above the rest, but more leveraged financed-focused Goldman Sachs and Morgan Stanley also had good years – as did Citigroup from a lower base.

Growth rates were similarly impressive in ECM thanks to their low starting point, with the five banks generating US$7bn of revenues between them. Year-on-year changes were more modest in advisory, with Goldman holding its leadership position despite JP Morgan making up ground.

Risk on

The record dealmaking fees of 2021 – another peculiar year, given the influence of the pandemic – illustrate the potential upside opportunity for banks this year. The more equity-focused houses of Goldman and Morgan Stanley are still 46% and 40% below their respective 2021 revenue levels. JP Morgan and Bank of America, by contrast, are down closer to 30% thanks to their higher exposure to DCM.

The bigger worry for bank executives is that any growth in investment banking fees may merely offset declines in their much larger trading businesses, which have expanded significantly in recent years.

The big five’s FICC trading revenues of US$68bn in 2024 were up 5% and only just shy of 2020’s record haul. Unsurprisingly, equities and credit (especially securitisation) led the way in the risk-on market environment. Equities revenues overall rose 19% on average to reach a record US$49bn.

Gaining ground

Goldman has been the biggest winner in sales and trading in recent years. It continued to gain ground in FICC in 2024, bringing its market share among the big five to 19.4% from a low of 13.7% in 2017. In equities it performed broadly in line with peers, but over the last three years it has increased its market share by more than 200bp to about 28%.

The strong growth in hedge fund business and in financing has played to Goldman’s strengths. While its FICC intermediation revenues have grown gradually over the past few years, financing revenues from its activities in private credit, structured and mortgage lending have almost doubled. In equities, Goldman’s market-leading hedge fund prime brokerage has proved similarly decisive, contributing 41% of revenues in 2024 compared with just over a third in 2021.

Mixed picture

Market share trends among its competitors have been more mixed in recent years. JP Morgan has held firm in FICC, but lost ground in equities. Bank of America has recovered previously lost market share, particularly in macro and credit trading. Morgan Stanley had a particularly strong fourth quarter, but over the medium term has not seen Goldman’s market share gains.

Citigroup had a stellar 2024 in equities and credit after losing market share in recent years, but its macro-trading business underperformed. The extent of the decline of Citi’s FICC franchise is evident when comparing 2024 with 2017 revenues. Over this period, it has gone from being roughly the same size of market leader JP Morgan to generating less than three-quarters the amount of revenue. In 2017, Citi’s FICC revenues were twice as large as Goldman's; in 2024 it was only about 10% larger.

Challenges ahead

The challenge for US banks in 2025 will be that market expectations for revenue and profit growth are very high, but it’s hard to see their trading businesses continuing their rapid pace of expansion. And despite the largest investment banks registering respectable returns on equity in 2024 (with the notable exception of Citi), none have hit the heights of the 20%-plus returns of 2021.

Even a small decline in trading revenues – if trading desks slip or there’s a pullback in hedge fund and financing activity – would wipe out any increase in banks’ underwriting and advisory fees. In stark terms, a 10% reduction in markets revenues (about US$12bn) is equivalent to a more than 50% increase in ECM and advisory fees.

In 2009, investment banks misjudged the outlook and started hiring like the boom years were back. This time they’d do well to remember that lesson and keep a firm handle on costs to ensure they can improve shareholder returns even without a rerun of blockbuster dealmaking years like 2021.

Rupak Ghose is a former financials research analyst