Rates desks less profitable despite trading boom

Bank trading desks are struggling to capitalise on the record volume passing through interest rate derivative markets this year, as fierce competition is tightening bid-offer spreads and compressing profit margins.

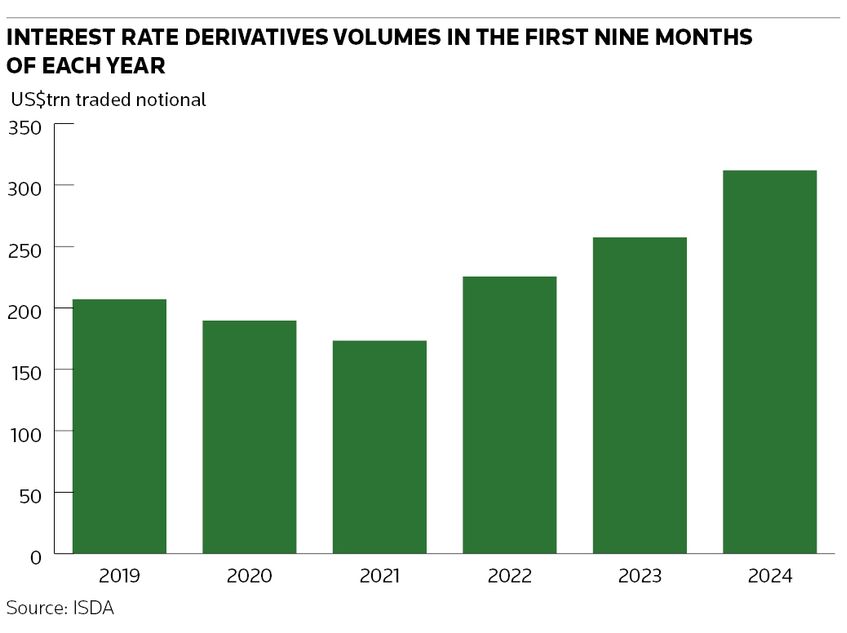

Interest rate derivatives traded notional reached around US$312trn in the first nine months of 2024, according to trade repository data collated by the International Swaps and Derivatives Association, a 21% increase from the previous year. But this flurry of activity hasn't translated into higher profits, with most major banks reporting declines in rates trading revenues this year.

That is because of the significantly tighter margins that rates trading desks have had to contend with, senior bankers say, as the combination of low volatility and banks vying for market share has fuelled a race to the bottom in prices, eroding profits in the process.

“2024 has provided the perfect storm for spread compression, which has really hurt trading desks and brought down their margins,” said Angad Chhatwal, head of global macro markets at analytics firm Coalition Greenwich. “There have been situations this year where banks have been happy to print trades close to or at mid-market – basically zero P&L – just to be able to maintain market share or notional share with clients.”

Overnight index swaps – short-dated derivatives that are used to bet on the direction of interest rates – made up the bulk of interest rate derivatives volume in the first nine months, growing by almost 23% to US$195trn compared with 2023, according to ISDA.

However, the biggest increase in percentage terms came from fixed-to-floating interest rate swaps, a longer-dated type of derivative that is popular with corporate treasurers and financial institutions. Volume in these contracts rose by almost 47% to around US$57trn in traded notional by the end of September.

Increased debt issuance is one factor that has boosted activity, said Olga Roman, head of research at ISDA, as many firms turned to derivatives to lock in a stable cost of funding. Global corporate debt reached almost US$24trn in July, according to analysis by S&P, a US$776bn increase from July last year.

Uncertainty over the trajectory of central bank policy has prompted investors and large corporates to use derivatives to manage their interest rate exposure. Political events have been another driver in a year that has seen large parts of the world hold elections. That includes a flurry of trading around the reelection of former US president Donald Trump as well as upheaval in the European political landscape following parliamentary elections in France in summer, the collapse of Germany's coalition government in November and the fall of France's minority government earlier this month.

"Bottom line, a lot of different factors were all converging towards more activity from various accounts, triggering this sharp increase in volumes," said the head of swaps trading at a European bank.

Compressed margins

The squeeze on margins means most banks have nevertheless reported declines in rates trading revenues despite the booming volume. The fact that certain important client types, such as hedge funds, have been less active in the interest rate derivatives market this year hasn't helped.

Senior traders also note the role of bank and non-bank market makers pumping greater resources into macro products over the past few years to capture an increase in revenues since the outbreak of the pandemic in 2020. That comes as central banks have raised interest rates and injected higher volatility into markets – a stark contrast to the ultra-low interest rate environment of the previous decade. Many rates trading businesses struggled to produce decent returns during that period, leading to a wave of cuts from banks in this space.

The increased competition to win trades shows how much banks have been reinvesting in rates trading. While a large bank would previously only have been competing with one other firm on products such as deal contingent interest rate swaps – a contract that is popular with corporates looking to hedge interest rate exposures stemming from a merger or acquisition – they’re now competing with three or four other banks, said Chhatwal.

“When more people are competing for flow, that pushes pricing down – hence margin compression,” he said.

There are, however, some encouraging signs for trading desks that the compression in spreads may be starting to ease, potentially paving the way for a better 2025 for rates traders.

“2024 was a low point for banks from a spread compression perspective but that now seems to have fully played out,” said Chhatwal – who said institutional clients started to become more active in the fourth quarter. “[That] should create a reversal in spread compression as there will be a lot more flow available in the market overall.”