Banks gain traction with reg cap trades

Banks are ramping up efforts to reduce the amount of regulatory capital they hold against derivatives trades, with many developing complex hedging arrangements to offload risks to specialist investors.

Citigroup, Deutsche Bank and Natixis are among several banks that have crafted bespoke hedges over the past year or so against so-called credit valuation adjustment risks, in which banks account for the possibility of losses stemming from exposures to derivatives counterparties. That comes amid a rise in the number of investors, from credit insurers to hedge funds to sovereign wealth funds, that are willing to get paid to take these risks off banks’ books.

These transactions come in different flavours but most have the same goal: finding a hedge for some of banks' thorniest (and often least liquid) derivatives exposures, while also releasing some of the hefty sums of capital that regulators require banks to set aside against these positions. That, in turn, can free up banks' credit lines and increase their capacity to do more business with clients.

“We are trading more idiosyncratic hedges with investors that are willing to share our risk,” said Mathias Hugly, co-head of wrapping and transaction optimisation at Natixis CIB. “These products are useful to improve our risk management. They are also efficient for our regulatory capital, extending our capacity to do business and take more risk with clients without a strong increase in our risk-weighted assets."

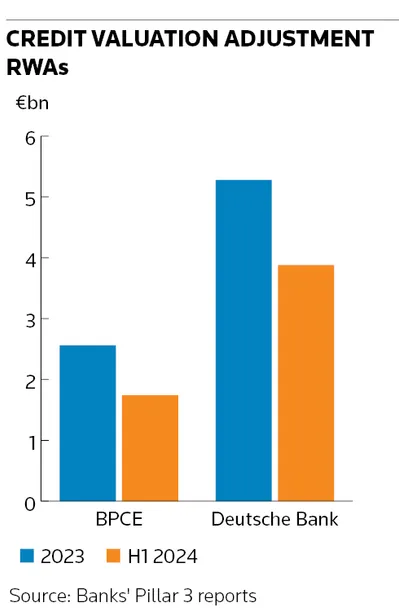

Groupe BPCE, the parent of Natixis, reported a €65m reduction in capital requirements after its CVA RWAs dropped by nearly a third in the first half to €1.7bn. Deutsche Bank reduced its CVA risk-weighted assets by €1.4bn in the second quarter to €3.9bn, its lowest level on record after putting in place hedges, freeing up €111m in capital. Spokespeople for Citigroup and Deutsche Bank declined to comment.

Reducing capital requirements has become an important focus for investment banks ahead of Basel III endgame regulations that are slated to start coming into force next year. Synthetic risk transfers have grown in prominence as a way for banks to transfer some of the exposures from their loan books to outside investors and many have also been working behind the scenes to lower the amount of capital they have to hold against their trading activities.

CVA has been one of the top priorities given the massive amounts of capital banks have to set aside against these exposures. That is particularly true for European banks because of the current scope of their regulations, but US banks also face greater incentives to find CVA hedges under the final Basel III rules.

Fluctuating risks

CVA risks for banks fluctuate in line with movements in financial markets. A deterioration in the creditworthiness of the counterparty on the other side of a bank’s derivative trade can drive its CVA higher in the same way a move in interest rates or currencies increases the value of the derivative contract for the bank, meaning it stands to lose more money in the event of its counterparty defaulting.

There are various ways that banks can hedge CVA, such as buying credit default swap protection against derivatives counterparties. The problem is that there isn't always an active CDS market for every company that banks deal with, creating demand for more bespoke hedging agreements to handle exposures. Dmitry Pugachevsky, head of research at risk and analytics firm Quantifi, said they have seen more bespoke CVA hedges over the past year and a half, with banks paying specialist hedge funds to take the risk off their books.

“Offloading it may be more expensive for banks [than buying and selling CDS] but it prevents them from having a CVA hedging headache,” said Pugachevsky. “CVA is one of the largest capital charges banks face so if they can reduce that capital charge by engaging in CVA hedges then that’s very beneficial for banks, especially because of how expensive capital is.”

These transactions can take several forms depending on a bank’s hedging needs and the firm's willingness to take on the exposure. Contingent CDS, in which the hedge is directly linked to a bank’s underlying derivatives trade with a counterparty, are popular because they can offer a more precise way for a bank to manage these risks. If a bank’s exposure to its derivatives counterparty increases as interest rates rise or fall, for instance, then the amount of CDS protection it has bought against the counterparty will also increase.

Other instruments that have become more common include financial guarantees, risk participation agreements and credit insurance, which can be designed to provide banks with protection against a percentage of their exposure, capped at a maximum. The dynamic nature of many of these arrangements makes them particularly appealing for banks.

“[These hedges] are very efficient because you don't need to rehedge as your exposure increases or decreases. It's a very good hedge,” said Hugly.

Risk rewards

Much of the focus is on long-dated uncollateralised exposures in which the bank's derivatives counterparty doesn't have an active CDS market. However, regulations also incentivise banks to hedge collateralised exposures to cover the risk of the bank not collecting enough margin before its counterparty defaults. These hedges tend to be more costly because banks don’t usually bake credit charges into the price of the underlying derivative contract in the same way they do with uncollateralised trades.

“There is absolutely value in hedging collateralised exposures but it’s more expensive because banks don’t charge [counterparties] for it,” said a counterparty risk specialist at a major bank. “Uncollateralised derivatives with names that don’t trade at all in the credit market have the best risk-return profile by far because you get an actual economic hedge and therefore get some capital relief.”

The complexity of these hedging transactions – which can take months for banks to thrash out with investors – helps explain why this kind of activity has been sporadic over the years. Bankers attribute the recent uptick to several factors. Russia’s 2022 invasion of Ukraine and the subsequent surge in energy prices created huge counterparty trading exposures for some banks, forcing them to find ways to distribute their risks.

More long-term investors, such as sovereign wealth funds and specialist credit insurers, have taken a greater interest in striking deals, with some reportedly establishing strategies dedicated to assuming banks’ Basel III trading risks. That is a timely development considering that the Basel III endgame, also known as Basel 3.1, is expected to increase banks' CVA hedging needs still further.

“While the main focus may be economic hedging, there’s a deliberate move from banks to try to be more capital efficient in terms of their CVA hedging strategies as we move into Basel 3.1,” said Tony Hall, global head of trading, markets at Standard Chartered.

“Basel 3.1 should give banks more flexibility as a wider array of credit hedges for CVA are eligible. There should also be more activity where banks go externally to hedge the market risk sensitivity of their [different derivative valuation adjustments] because of changes to the regulations."

Additional reporting by Natasha Rega-Jones