End of the easy money: rate cuts will hit corporate and investment banks

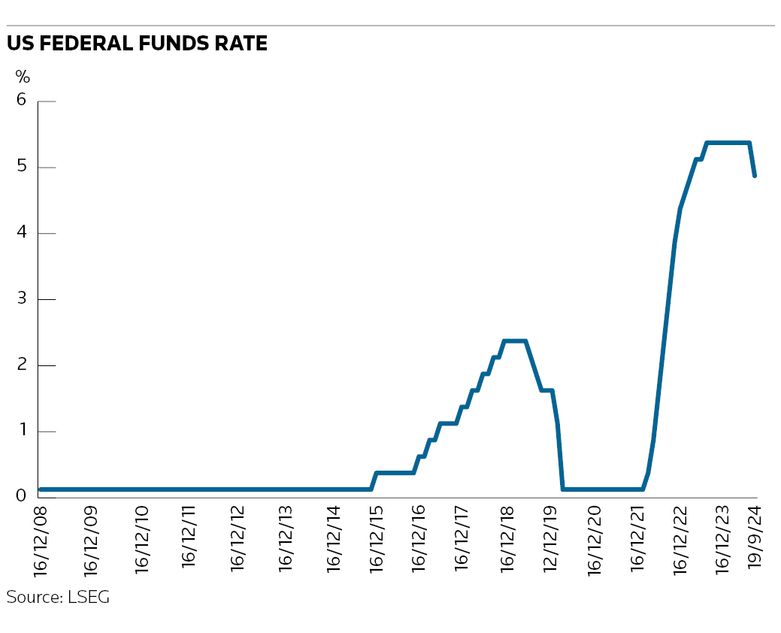

When the US Federal Reserve cut interest rates by 50bp – to 4.75%–5% – you would have been forgiven for expecting bank stocks to fall given that they have benefited from the move to higher interest rates over the past few years (especially considering that the futures market is suggesting a Fed funds rate of less than 3% by the end of 2025).

In fact, bank stocks rose, presumably because investors think the rate cut reduces the risk of a recession and therefore lessens credit risks. For bank investors it was a case of heads you win and tails you win.

But there will be earnings pressure from the drop in interest rates – and it will be concentrated on the mega banks that have benefited most from the easy money that comes from being able to hold deposit rates down as interest rates rose.

When it comes to the headwind (or tailwind) of net interest margin, the retail banking business gets the most attention, and yet the interest rate exposure of the largest corporate and investment banking divisions shouldn’t be underestimated.

Citigroup, for example, made a big noise about its newly constructed “services” division in June 2024 even though the underlying growth in this business – which includes transaction banking and security services – has been sluggish at best in recent years.

That the division had something to shout about was essentially the consequence of net interest income that almost doubled between 2021 and 2023 to US$13.2bn and continued to grow this year. In the first half of 2024, the NII of US$5.4bn in the transaction bank was flat year on year but the securities services side saw NII grow 15% to US$1.2bn.

A similar trend could be seen at other leading corporate and transaction banking networks. For instance, JP Morgan’s payments business added around US$4.5bn of revenue owing to higher interest rates in 2023 and these remained at elevated levels in the first half of 2024.

Most dramatically, all of Bank of America’s global banking business revenue growth last year was driven by the addition of US$2.5bn of NII (although some of this has been given back in the first half of this year). Net interest margins for the division expanded from 2.26% in 2022 to 2.73% in 2023. Its NIM in the first half of 2024 was 2.44%.

Certainly margins across these units will be pressured by lower rates.

Mixed picture

Despite the Dodd-Frank regulations that were designed to ensure that investment banks' markets divisions were all about transactions for third parties rather than prop trading, NII still plays a significant role in the profitability of these units, although the picture is more mixed and disclosure on underlying drivers is opaque.

NII is generated typically by the offset between high-yielding assets that the trading desk is warehousing temporarily and the bank’s funding costs. An additional complexity is that trading desks are likely to have offsetting derivatives positions that create gains and losses on the principal transaction line of the P&L.

This could be revenues from hedging or market-making that have an associated cost of funding. Hence NII tends be generated in FICC while equities can be a drag.

The biggest numbers come from Citi, which reports NII contributing over one-third of its markets revenues. This NII increased by 25% in 2023 on 2022 to US$7.3bn and is up 5% in the first half of 2024.

Bank of America’s markets business is annualising at around US$3bn of NII, albeit there has been some volatility in this in recent years.

JP Morgan’s markets business has seen NII fall from US$8bn in 2021 to around zero in the last 18 months. The FICC component of that number is much healthier (US$7.1bn in 2021 and annualising slightly above that in the first half of 2024), presumably because it is benefiting from higher rates. That suggests, though, that the equities component largely wiped out FICC’s NII contribution and indeed the bank highlighted higher funding costs as driving a large negative number in equities.

The significance of NII in FICC businesses of investment banks can also been seen at Goldman Sachs and Deutsche Bank – two firms that have been successfully expanding their FICC financing businesses in recent years.

Goldman’s markets business saw NII double in the first half of this year to US$1.2bn (relative to the first half of 2023) with all of it coming from FICC. Deutsche saw NII stay flat at €1.3bn in the first half of this year (compared to the first half of 2023) with a healthy net interest margin of 2.8%.

Market prices have moved ahead of the Fed, but low interest rates will definitely dampen some of the fastest growing parts of corporate and investment banking such as transaction banking, securities services and FICC financing. And those numbers show there is certainly a lot of easy money at risk of disappearing.

Hence it isn’t surprising to see the likes of Goldman announcing cost cuts or the new HSBC CEO looking to streamline further its business.

Rupak Ghose is a former financials research analyst