“Lots of debate when VC/IPO markets will ‘open’ – but they are wide open today. The restraint to deals are inflated price expectations by boards incorrectly anchored to a zero-rate world. Get fit, get sober, and get liquid. Price clears all markets.”

These could have been the concluding remarks of every ECM banker in every IPO pitch over the past couple of years but was, in fact, what top venture capital investor Brad Gerstner tweeted in late 2023.

And yet it’s not clear that VC investors are listening. Or that they are under particular pressure to take the necessary hit on valuation to get deals done.

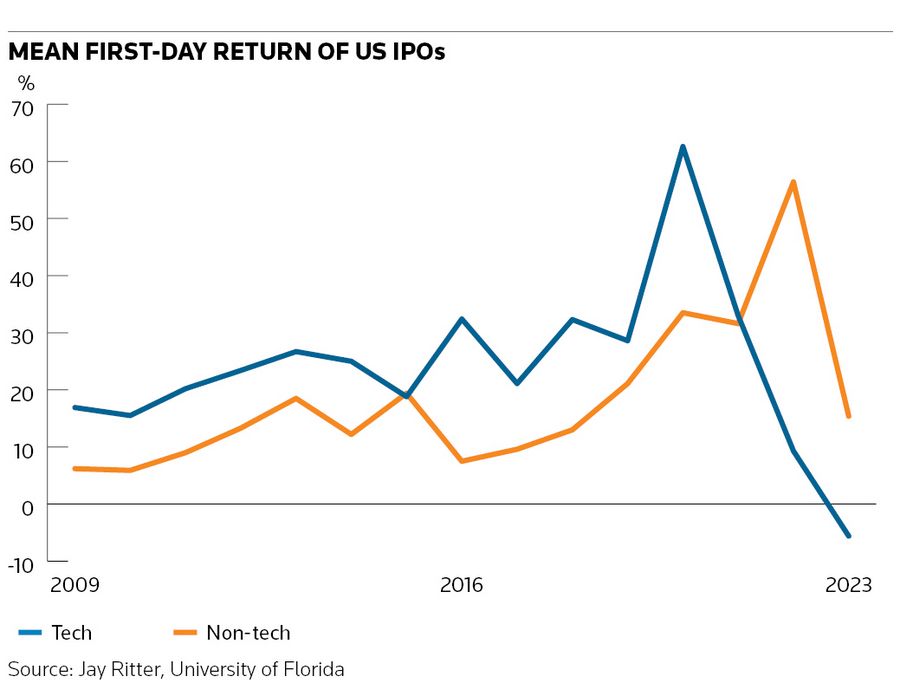

According to data collected by Jay Ritter, a finance professor at the University of Florida, multiples for VC-backed tech IPOs peaked at around 20 times revenues in 2021 and almost halved to 12.7 times in 2023. But, presumably as a result, VC-backed tech IPO activity on Nasdaq has been muted – with only four deals this year.

According to Ritter’s data, the average number of US VC-backed tech IPOs in the 2010–2020 period was 30, which was followed by a blockbuster year of 77 IPOs in 2021, and then the drought of only one IPO in 2022 and four in 2023.

In fact, the number of IPOs of tech companies has been structurally shrinking for a long time. VC-backed tech IPOs in the US hit a record of 250 in 1999. But as a tsunami of money flowed into VCs and growth equity, companies delayed listing and spent an extended period of time in the private markets.

The median age of a tech company at IPO has doubled from five years in the late 1990s to around 10 years today, according to the data, and the average size has increased from revenues of US$20m–$50m at IPO to US$150m–$200m.

More attention, more scrutiny

That means that companies that do come to the IPO market will receive more attention and greater scrutiny of their financial performance from potential investors than was once the case. And, on the other side of the coin, that venture capitalists and growth equity investors, who have written huge cheques or are sitting on significant paper gains, have even more to lose.

Take the examples of some of the largest privately held fintechs like Stripe, Revolut and Monzo.

Sequoia, one of Silicon Valley’s premier venture capital firms, has invested US$517m in Stripe since seeding it in 2010. Sequoia’s stake in Stripe is worth US$9.8bn on Stripe’s July 2024 valuation. That is a lot of money at risk.

With the architects of Stripe, the Collison brothers, not ready to go public and a valuation well above Stripe’s peers, Sequoia is continuing to kick the can down the road. Indeed, having already invested US$139m in Stripe’s recent tender offer, Sequoia is offering to buy up to US$861m of Stripe shares from its “legacy” 2009–2012 funds at a valuation of US$70bn. Stripe has also conducted a series of primary fundraisings to fund buybacks that provide liquidity to employees.

The return of secondary sales that allow management to crystallise value without an IPO is also reducing the necessity of listings.

At Revolut, two large crossover funds (Tiger Global Management, which together with SoftBank led the US$800m Series E primary raise at a US$32bn valuation in 2021, and Coatue Management) led a secondary offering to buy shares worth US$500m in Revolut at a valuation of US$45bn. This is only from current employees – ie, not former employees or other shareholders. Given the limited number of employees with significant amounts of stock it is likely that a huge portion of this US$500m will go to the two Revolut founders, Nikolay Storonsky and Vlad Yatsenko.

The terms of private fundraising rounds are rarely disclosed publicly and often include anti-dilution provisions protecting new investors from down rounds, so are difficult to compare with public market valuations. In this case, Revolut’s profits are the same as publicly listed competitor Wise, but its valuation is five times higher.

A third candidate for IPO among the fintech unicorns is Monzo, which instead has raised US$610m from investors this year at a post-money valuation of US$5.2bn from top venture firms and corporates like Alphabet’s growth fund.

There are clear pressures on VCs – especially those without the deep pockets of the industry leaders – to move companies into the public markets. Stripe is unusual in that it is almost 15 years old and with the average time before an IPO for VC-backed tech companies hitting around 10 years, many VC funds are coming near to the end of their 10 to 15-year time period, when limited partners are expecting to see a fully exited portfolio that returns their cash.

Nonetheless, the big valuation gaps between private unicorns and their public peers – plus the return to private investing by crossover funds encouraged by the strength of Nasdaq – remains a major drag on the IPO market.

Who will sneeze first is hard to say but many privately held unicorns need to do a lot more growing before the public markets are likely to match their existing valuations.

Yes, price clears all markets – but only if there are willing buyers and willing sellers.

Rupak Ghose is a former financials research analyst