Citi seeks ratings to take loans to private credit funds mainstream

Citigroup is working on securing credit ratings for senior loans it makes to direct lenders to create more of a syndicated market where the bank can distribute these exposures to a wider range of investors.

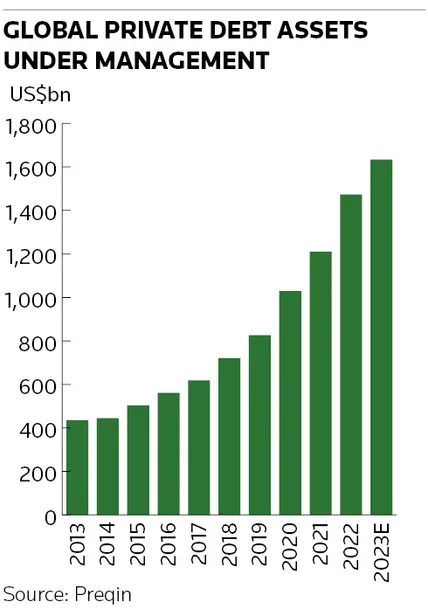

The move comes amid a mushrooming in private credit markets over the past decade, coupled with a sharp rise in the amount of financing that banks provide to direct lending funds so they can leverage their portfolios of loans to middle-market companies.

The plans to encourage more investors to put their money into these senior loan facilities shows how banks’ financing desks are struggling to keep pace with the rapid expansion of direct lending – and how these funds are becoming more deeply intertwined with the broader financial system.

“Private credit markets are growing at 8%–10% a year, but bank balance sheets clearly aren’t growing at that rate,” said Mickey Bhatia, Citi’s head of spread products. “Banks are now looking to create more of a syndicated market out of their senior loan book, but you need to get ratings in order to maximise the distribution of these loans.”

Bhatia outlined the plans during a wide-ranging interview with IFR in which he discussed how Citi is adapting its credit trading and financing businesses to these rapidly evolving markets. Parts of Citi’s “spread product” unit that Bhatia oversees have found themselves in the crosshairs over the past year or so as chief executive Jane Fraser has looked to improve shareholder returns across the bank.

Citi has shuttered its municipal bond trading and special situation distressed trading desks as part of the latest overhaul and has made cuts to its European leveraged loans business. The bank has also brought the bulk of its financing and securitisation activities, which previously sat between markets and investment banking, within its markets division. Private financing is where Bhatia believes the best opportunities lie in the years ahead.

“The market has changed. In corporate bond trading the wallet [industry revenue pool] has declined sharply since 2020,” he said. “Private financing is where the growth is. These funds are growing and they need leverage, so they come to us for financing.”

Private credit opportunity

Assets in private credit funds have increased nearly four-fold over the past decade to US$1.6trn, according to data provider Preqin, as direct lenders have replaced banks across large parts of the economy. Banks’ financing arms are benefiting from this expansion. Analysis from the Federal Reserve Bank of New York shows the amount of term loans banks make to non-bank financial institutions has risen materially over the past decade to account for more than a quarter of their total lending.

Bhatia said senior loans to private credit funds attract risk-weighted capital of 20% for banks – a level he described as “optimal”. These financing facilities are typically secured against the assets of direct lending funds or against the funds themselves. The seniority of the loan provides banks with a thick layer of insulation against default in the underlying direct lending portfolios, making it resemble the senior tranche of a mid-market collateralised loan obligation.

Unlike a CLO, though, these are not securities – and banks don’t need ratings for loans that sit on their balance sheets. Banks already sell some of their exposures to clients like pension funds that don’t require ratings on their investments. This usually involves the bank retaining 51% of a senior loan it has made to the private credit fund so that it is responsible for servicing the debt and has a strong incentive to keep robust underwriting standards.

Distributing more of this risk would free up capacity for banks to make new loans and continue catering to the surge in demand for financing from private credit funds. Securing ratings for the loans is an obvious step because it would open the door to investors like insurance companies, which typically require a ratings agency’s stamp of approval before parting with their money.

“We believe most of the senior lending market [to private credit funds] will become a rated market. It won’t be a full-scale public market like Triple A CLOs. But you’ll see more of these deals getting syndicated to clients,” Bhatia said.

Lurking risks?

Bhatia said banks get far more information about the exposure in the portfolios and funds that they finance compared to if they were buying public securities, because they are the lenders. Even so, private credit’s breakneck growth has raised questions about potential risks in these markets.

Bhatia said he’s not worried about a potential mismatch in the assets of these private credit funds and their liabilities. “Leaving aside the retail funds, it’s all long-term capital investing in these funds,” he said.

A greater concern, in his view, is the proliferation of small private credit managers that might not have the resources to deal with soured loans if defaults accelerate.

“Banks have very big workout divisions – they’ll never come and liquidate these troubled loans at a fire sale price. But if you’re a smaller asset manager, that’s an issue. In our direct lending business, we’re very careful about who we underwrite and we mostly deal with big managers,” he said.

Flow overhaul

Citi’s expansion in private financing contrasts with cuts it has made to parts of its credit trading operations, where the bank buys and sells corporate bonds and related instruments on behalf of clients. In muni trading, an area in which Citi used to be one of the largest banks, Bhatia pointed to a combination of increased competition and the high staffing costs of running the business to explain the bank’s exit.

“It became more competitive and the bid offers became smaller,” he said.

Shrinking bid-offer spreads are one of the drivers behind Citi’s flow trading cuts more broadly. Bhatia suggested this is a structural shift resulting from the rise of exchange-traded funds and passive investing becoming more prominent in credit markets.

“There just aren’t that many folks trading actively any more,” he said.

Bhatia said Citi spent a long time establishing what is the optimal amount of capital and RWAs for the flow trading activities it needs to support its clients and primary underwriting businesses. Citi said it is still committed to being among the top three or four dealers in its core businesses such as trading investment-grade, high-yield and emerging market bonds, as well as securitised products like CLOs and RMBS.

“You cannot aim to be number seven in a trading business – you’ll definitely lose money because you don’t know where the flows are. You need scale,” he said.

Non-bank market-makers like Jane Street have made serious inroads in credit trading in recent years thanks to their prowess in algorithmic trading. That has complicated the competitive landscape for banks, while also pointing to the future of how these markets may evolve.

“It’s a big issue for banks,” Bhatia said, while noting the liquidity these firms provide can also be helpful when banks need to offload risk.

“The market is going to fragment. All-to-all trading will be there if you need liquidity. But if clients are doing a large trade, then RFQs [request-for-quotes] will be directed to a limited number of dealers. And we plan to be one of them,” he said.