UK authorities scrutinise how banks made billions in tax-free pounds from complex inflation trades

Some of the world’s largest investment banks made hundreds of millions of pounds in tax-free revenues in recent years through a series of complex financial trades that have drawn scrutiny from UK authorities.

Barclays, Goldman Sachs and JP Morgan are among the banks to boost their income significantly – and cut their effective UK tax rate – through investments in UK inflation-linked government bonds. Those positions were often hedged – either directly or indirectly – with derivatives contracts or other positions that helped insulate the bonds against adverse market moves, according to sources familiar with the matter.

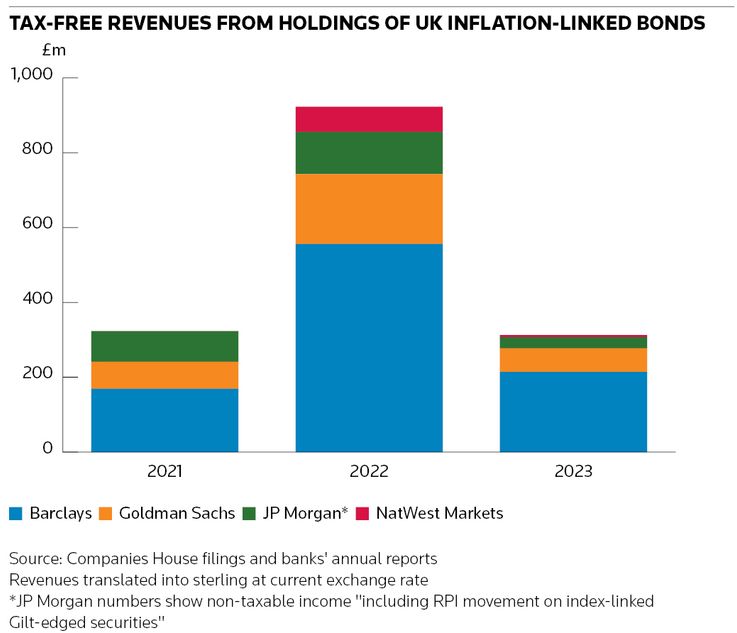

These trades helped banks preserve huge tax-free gains – which came from an uplift in the final payout on inflation-linked bonds following a sharp jump in UK consumer prices – by significantly reducing the risk that those positions would lose money as interest rates rose. In total, banks made about £1.6bn in UK tax-free revenues from holding inflation-linked government bonds – known as linkers – between 2021 and 2023, public filings show.

Barclays reported £939m of UK tax relief on holdings of inflation-linked government bonds over that period, while Goldman reported UK tax-free income of US$411m on inflation-linked government bonds. JP Morgan reported US$286m in non-taxable UK income “including RPI [inflation] movement on index-linked Gilt-edged securities” during those years.

There is no indication that the banks contravened UK tax law. However, HM Revenue & Customs, the country's tax authority, has frowned on aspects of some of the inflation-linked trades where it believes banks held hedges that helped maximise the tax-free gains on their holdings, sources said. HMRC has warned at least some firms against these practices, but will not try to recuperate any of the tax savings, sources said. Barclays was one firm that was told to stop the practice, sources said.

“There was a slap on a wrist and they were told they’re not supposed to do this,” said one source with knowledge of the transactions.

A spokesperson for HMRC declined to comment, citing taxpayer confidentiality, and said that the tax agency could neither confirm nor deny that any such transactions had drawn its attention. Spokespeople for Barclays, Goldman and JP Morgan declined to comment.

Historic opportunity

The UK's £618bn linker market, one of the world’s oldest and largest, presented traders with a historic opportunity between 2021 and 2023 when consumer prices were rising at their fastest rate since the 1980s – but it was one that was also tempered by great risk.

Investors could make huge gains from one of the defining features of UK inflation-linked government bonds: that their principal (the money they return to bondholders when they mature) grows in line with inflation. This uplift increased the outstanding amount on all UK linkers by £126bn in the three years to the end of 2023, according to data from the UK’s Debt Management Office. Such gains are, in most cases, exempt from tax.

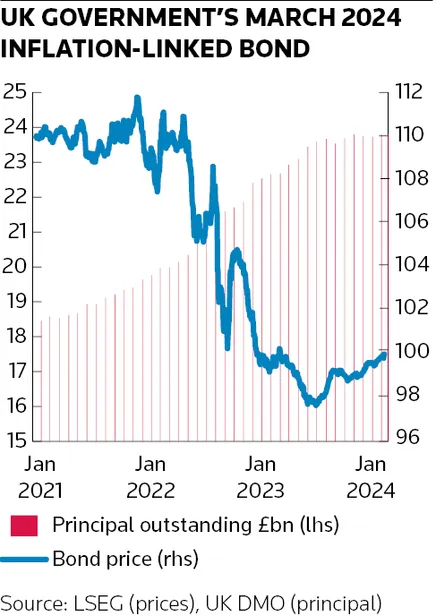

But the inflationary forces that promised to produce such heady returns also set in motion a treacherous combination of market dynamics that would crush bond prices and threatened to erode those gains – or wipe them out completely. The Bank of England raised interest rates rapidly in a bid to curb inflation from late 2021 and that sent bond prices tumbling, with the ICE BofA UK Inflation-linked Gilt index losing about half its value between then and its low in September 2022.

Traders say these conflicting forces made holding some form of offsetting exposure, which would neutralise the risk of rising interest rates denting the value of linkers, essential to generate material tax-free gains.

"There is a common misconception that buying linkers will protect you against inflation. The problem is bonds will sell off in a high inflation environment,” said a senior trader with knowledge of the inflation trades. “You can, in theory, replicate the cashflows of a linker using inflation swaps to build a synthetic structure that would offset a decline in linker prices. But some of these structures require expert knowledge.”

The problem for banks was that an offsetting hedge, if directly linked to their bond holdings, could mean that the tax-free status on the investments under HMRC rules no longer applied. Its guidelines say that companies are only eligible for the linker tax relief provided they aren’t party to a scheme that is designed specifically for hedging any of the economic exposure to the linkers.

Banks regularly use derivatives to manage their exposure to interest rates and inflation on their trading desks and other parts of their operations, making it hard to establish whether a deliberate linker hedging scheme had been put in place, sources said. Many banks, for example, will deploy large macro hedges to cover a range of different exposures. More broadly, hedging against rising rates was a major focus for banks at that time as central banks around the world tightened monetary policy aggressively to fight inflation.

Different approaches

Some banks took far bigger positions in UK inflation markets than others. Barclays reported £556m of UK tax relief from holdings of inflation-linked bonds in 2022, equivalent to about 10% of its revenues in fixed-income trading. Barclays, the sixth largest UK taxpayer in 2023, according to accountancy firm PwC, has substantial holdings of UK government bonds for its regulatory liquidity buffer as well as for its trading activities.

The gains at Goldman and JP Morgan came from linker positions held on their trading desks, sources said, through which the banks buy and sell securities on behalf of clients. That client demand rose in 2022 as inflation accelerated. Sources close to the banks denied the existence of specific schemes for hedging their linker exposure to take advantage of the tax-free gains. One source said that it is standard practice for banks to own bonds and manage their interest rate exposure with other instruments.

NatWest Markets reported tax-free income of £67m on UK inflation-linked government bonds in 2022 and another £6m in 2023. The UK bank checked with HMRC to ensure it was happy with the tax treatment of its linker holdings, one source said. Citigroup registered much smaller gains than its US rivals, according to sources. The US bank said in filings it had made US$42m in non-taxable UK income in 2022 without providing further details, up from just US$2m a year earlier.

Spokespeople for Citigroup and NatWest Markets declined to comment.

Tax-efficient angle

Senior traders said banks took different approaches to UK inflation investments. Focusing on shorter-dated linkers, which are less sensitive to changes in interest rates, was one tactic. That would also ensure the banks realised profits as soon as possible from trades resulting from the increase in principal.

Take the example of the UK’s linker that matured in March. The inflation-related uplift to the bond’s principal meant it paid out almost £24bn to bondholders when it was redeemed, £5.3bn more than it had promised at the start of 2021, according to the DMO. But bondholders still had to weather a decline in the price of the security, which fell from about 112% of face value in late 2021 to a low of 98% last year, before it was redeemed at par. Longer-dated securities experienced far bigger declines.

Entering derivatives contracts such as inflation swaps is one way banks could hedge their linkers. There was a surge in UK inflation swap trading in 2022, according to trade repository data collected by ISDA, with notional volumes rising 55% to US$1.1trn from a year earlier. The US inflation swaps market, by comparison, only grew by 10% over that period.

"Inflation bond cashflows are mostly back-ended by design: the main benefit comes at redemption,” said the senior trader with knowledge of the inflation trades. “For that reason, there's an obvious angle for linkers to be more tax efficient than conventional bonds. Banks that are involved in trading Gilts can set up strategies that look to take advantage of this tax relief.”

The return of inflation

Sovereigns have linked bond payments to inflation for decades, often providing tax breaks to encourage people to buy their debt. Activity in these markets rocketed after price rises accelerated in the aftermath of the pandemic and the war in Ukraine began, helping banks rake in huge revenues from inflation trading more broadly.

“There was increased activity [in the inflation markets] on the back of the big inflation shock that we had in the market. Many end-users with discretionary investments, who had in effect taken the view that inflation would remain low and had thus avoided the inflation markets, then sprung into action,” said Dariush Mirfendereski, co-head of flow and structured rates for EMEA at MUFG, which has not engaged in UK inflation trades.

Cooling UK inflation means that the opportunity some firms identified in UK inflation-linked bonds has faded. The annual RPI rate, an older measure of inflation that the linker market references, slowed to 3.3% in April from its October 2022 peak of 14.2%.

That has slowed the growth in the principal of UK linkers. The outstanding principal of the UK’s 2026 linker has grown by £317m this year, according to the DMO, compared with about £838m over the same period in 2022 when inflation was higher.