Tougher capital rules due to go live next year are stoking concerns that the business of banks clearing trades in the US$715trn derivatives market could reach dangerous levels of concentration, amplifying systemic risk when regulators are pushing more activity into clearing than ever before.

Proposed rules could force the largest US banks to increase capital levels by more than 80% for providing derivatives clearing services to clients – the equivalent of US$7.2bn per institution, according to analysis by the Futures Industry Association – while global banks would also see capital rise by 22%. Industry insiders warn that will put further strain on a market that is already near breaking point after mounting costs have prompted a wave of exits in recent years.

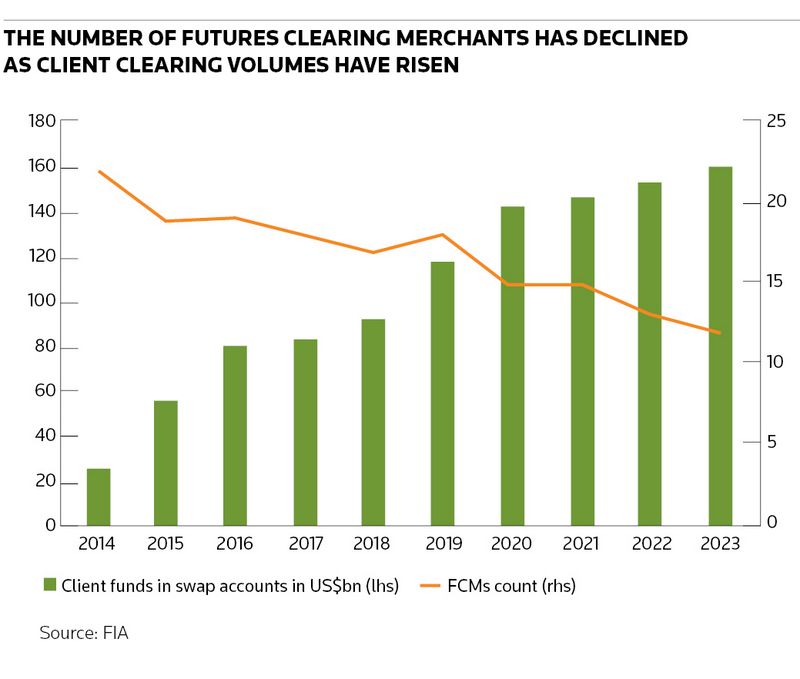

Only 12 banks provide over-the-counter derivatives clearing services in the US – a near 50% drop from a decade ago – with six firms accounting for 84% of activity. Banks are wary of any regulations that could erode that capacity further, not least because of a regulatory drive to push yet more activity through clearinghouses, including the US$27trn Treasury market.

“If any one of [the big six US clearing firms] reduces the amount of client clearing it supports or exits the business completely as a result of these rules … then the world has a big problem,” said Jackie Mesa, head of policy at the FIA. “There just are not enough [clearing brokers] to go around so there’s a delicate balance that regulators have to achieve.”

Global regulators have pushed as much derivatives activity as possible through central counterparties over the past 15 years in one of the landmark reforms following the 2008 financial crisis. Clearinghouses act as intermediaries in financial transactions to prevent losses cascading through the system if an important financial institution collapses.

Investors, such as asset managers and insurance companies, rely on banks to clear trades on their behalf because of the onerous requirements of becoming a direct clearing member. Banks charge for this service, with the client clearing market worth an estimated US$1.4bn in revenues each year. Fees aside, the largest banks tend to view clearing as a critical function thanks to its ability to cement relationships and help win additional business.

“Competition among all banks is quite fierce,” said Thomas Treadwell, EMEA head of clearing and FX prime brokerage at Citigroup. “This business is seen as a strong pillar to stand on for developing broad firm-wide relationships with clients.”

Not so crowded market

Even so, client clearing is an expensive and complex service to maintain. As well as having to set aside hefty amounts of regulatory capital against these businesses, banks must invest heavily in technology and systems to handle the large volume of client trades passing through their pipes.

A 2022 paper from global regulators found the risk management requirements for clearing OTC derivatives are “substantially more burdensome” than those for futures clearing. It also found some firms will provide clearing services even though they don't meet internal return on equity targets.

As a result, only the largest banks tend to offer services while many others have decided it’s simply not worth the trouble. Credit Suisse, Deutsche Bank, Nomura, BNY Mellon, State Street and NatWest are among those to have quit the business in recent years.

“We understand that client clearing is a low-margin business, and it is hard to get a good return on equity," said Ulrich Karl, head of clearing services at the International Swaps and Derivatives Association. “The market has become a lot smaller in terms of the number of banks offering client clearing, while the volume of derivatives that is cleared through the client clearing model is higher than ever before – putting a strain on the banks that continue to provide this service."

Because of the amount of additional capital US banks will have to cough up, the new rules are causing market-wide disquiet. Helen Gordon, global head of derivatives clearing at JP Morgan, said that while it seems unlikely that any of the top clearers would completely shut their client offering if the proposals are enacted, there is a good chance of a reduction in clearing capacity overall. That could lead to an increase in costs and reduced hedging activity as a result, she said.

Any clearer?

The rising pressure on banks in these markets comes as more of their customers are being forced to clear their financial transactions. A clearing exemption for European Union pension funds expired last year and a similar exemption for UK pension funds is set to end next June. In the US, mandatory clearing for Treasuries is due to go live from the end of 2025.

Institutional investors are already worrying about how a bump in clearing costs could filter through to them. Any US bank having to hold an additional US$1bn in capital under the new US rules would have to increase their net income from clearing by up to US$150m to meet an annual return target of 15%, according to the FIA.

Guy Whitby-Smith, head of solutions portfolio management at Legal & General Investment Management, said the cost of clearing plays an instrumental role in pension funds deciding whether to use swaps or government bonds to hedge their interest rate exposures. “These rules could reduce overall appetite for clearing swaps among the clients that are hit from increased capital costs faced by the banks.”

New entrants

Not everyone is sounding the alarm over beefed-up capital requirements. Some believe the US proposals could help reduce concentration by redistributing activity towards European banks and firms outside the banking system that are looking to grow their OTC clearing franchise.

“The European bank sector and non-bank sector has the capacity to absorb quite a lot of the potential overflow of clearing capacity from banks that will be impacted by these rules,” said Thomas Texier, head of clearing at Marex, a non-bank clearing broker.

Marex said it has expanded its exchange-traded futures and options client clearing service by about 13 times over the past five years to US$13bn in average client assets in 2023. “We’ve become more involved in the market and have already taken up capacity, but we can take a lot more and we have the ability to increase our scale," Texier said.

Many bankers say they’d welcome a more evenly distributed market in client clearing. But they also warn against any regulatory pressure that results in a reduction in clearing capacity from the large incumbent firms that have come to dominate these markets.

Such a scenario could have dire implications for systemic risk, they argue – the very thing that clearing is designed to mitigate. That is because clearinghouses rely on their members to help them weather periods of severe market stress and take on client trades that need to be moved and absorbed if another clearing broker is on the point of collapse. For the clearing system to remain healthy, it needs to retain enough institutions that can step up when the going gets tough.

“The whole market benefits from a balanced clearing system with multiple clearing firms,” said Gary Saunders, global head of prime derivatives services at Barclays. “I want Barclays to have a successful client clearing business but not to the extent that we’re the only ones clearing anything and no one else is involved. That would be a terribly bad situation to be in from a systemic risk perspective.”