Eurobond markets: from characters to calculations

After nearly 40 years in DCM, Chris Tuffey recalls the highs and lows and examines how things have changed. The thrill of the deal is still there, but perhaps not quite what it was.

In late 1986, after London’s “Big Bang”, I was lured from a prospective career in medicine to the glamour of the bond markets.

The leading Eurobond houses were where the “Masters of the Universe” plied their trade at the time. The market was a battlefield of small investment banks going head-to-head with big banks with many names now consigned to the history books – with Swiss Bank Corp, Morgan Grenfell, SG Warburg, Kidder Peabody, Paribas, Salomon, Shearson Lehman and, most recently, Credit Suisse, either swallowed up or bankrupt.

The survivors, despite a wobble or two, are now thriving.

At that time the market allowed the brave, the eager and the foolish to compete. Banks would buy a deal outright and then form as large a group of syndicate banks as needed to distribute the risk (groups of up to 40 banks were common) – the ability to sell the bonds wasn’t a necessity to win. It was about belief, reputation (league tables were effective) and, most importantly, risk appetite.

When I arrived bright-eyed and bushy-tailed on the syndicate desk at what was then CS First Boston, I was surrounded by market legends: Carter, Beck, Molson, Tine, Francioni, and then Walsh and Meadows – and above them all, the father of the market, Hans-Joerg Rudloff. All larger-than-life characters with a passion for winning; smart, aggressive and scarily convincing.

I learnt from the best, and the thrill of the deal rubbed off. Nothing beat watching deals being bought unhedged and then launched into the market days later, or announcing three separate deals simultaneously, all linked with back-to-back swaps.

Gone to pot

The market started to shift in 1989 when New Zealand pioneered the fixed reoffer system from the US, starting the move towards negotiated transactions and fewer bought deals.

Later, US-style pot syndication would make bought deals a rarity. The move has made the issuance process simpler, easier and more transparent. It has, however, meant that banks' appetite for risk has seen a marked reduction in the last 25 years, which is a shame, as buying deals was the best part of the job.

The feeling of a deal being 20 times oversubscribed and squeezing 25bp from initial price thoughts pales against taking down a 20-year corporate bond during the Cypriot banking crisis or buying an Additional Tier 1 bond at 2am that had been pulled the previous week.

Nor does delivering a message to the client that we have tightened their deal a basis point inside their target give the same buzz as telling them we stand behind them when our joint leads are scrambling for conviction (or approval) to proceed. These are things that have made the job fun and exhilarating.

Faking it

You cannot win every time, so you swallow the losses and tell the stories later. We’ve had Eastern European corporate deals where half the orders were fake and an Indian FRN which I mispriced by so much that it closed the market – not good days. Elsewhere, nightmare tales of a Latin American deal which cost one syndicate manager his job and another who suffered an even worse fate: he was moved to sales.

Issuers felt aggrieved if their deal appeared in the pages of IFR describing it as a mispriced shambles, so demanded we fix it.

Historically, new issue bonds were traded by the syndicate desk. It was one of my first jobs and many of my peers cut their teeth the same way. Banks would then “stabilise” deals – the practice of supporting a deal’s performance in the “grey” (pre-issue) market.

Leads would either overallocate or buy bonds back from the syndicate banks to keep an orderly market. When we launched the Bank of England’s first jumbo US dollar deal, the market was so volatile that the head of syndicate at the other lead sought divine support at 4am during bookbuilding.

As it was, the deal sold well and we overallocated by US$1bn to ensure its performance – impossible in today’s market.

Stabilisation could go wrong though: a notorious TMCC ECU deal ended up with the lead owning 120% of the issue in a few short hours. Curiously, stabilisation in new bond issues is all but over.

Innovation

The debt market could never be accused of a lack of progress and as the derivatives market came of age in the 1990s, it opened the market to new borrowers and innovative structures. Initially, we were joined at pitches by well-spoken derivatives marketers with Hermes ties, gold watches and a thorough knowledge of an HP12C calculator. Now analysts know how to pitch derivatives before they leave university.

The seismic events of the global financial crisis in 2008 forced creative solutions to real-world problems. Credit Suisse helped drive the CoCo (or AT1) market following Lehman Brother’s collapse and then we got to see them up close doing what they were designed to do, at least in part, in March 2023 when Credit Suisse went into the history books. Think also of sukuk issuance and green/sustainability-linked bonds helping diversify funding sources.

The market, however, also came up with solutions to problems no one knew existed. The Dragon bond market, anyone?

The market will continue to innovate and create solutions but given the commoditisation of the product over the last 40 years, DCM is now considered part of a suite of treasury products offered to clients rather than the leading value-added investment banking product it was.

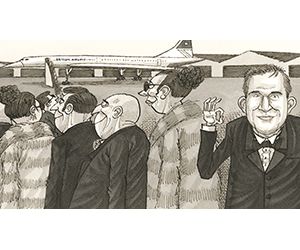

Concorde to coach

As the business became more commoditised and the previous generation of bankers disappeared up to the executive floors, asset managers and golf courses, life began to change. P&L volatility and huge risk positions were things you only talked about and then there were the changes to T&E. The transatlantic Concorde flights, internal conferences in remote Philippines islands and syndicate drinks in St Tropez made way for flying economy in Europe, in-house conferences in New York and the legendary RBS Burns Night syndicate drinks. Travelling coach short-haul and mandatory compliance training killed in-flight working; seeing the bonus pool of a competitor’s capital markets team while on an early flight back to London from Frankfurt is a thing of the past.

You scratch my back …

The biggest developments over the past 40 years in the primary market are those aspects of the business that drive success and the ability to win deals. Far from innovation, risk appetite or a great lunch, it’s reciprocity. Issuers use it to help decide which banks lead their bonds.

SSA borrowers appoint dealers that provide treasury orders and create secondary market liquidity. Corporates rarely choose leads from outside their lending group. Banks award mandates to other banks for which they lead deals. Issuers analyse their fee wallet, not only to ensure they are getting value for money but to ensure access to the most valuable resource: capital.

Best job

I have long said, as many would attest, that syndicate is the hardest job in the bank. But as I was told by one career sage in 1989 “slinging bonds in syndicate” is also the best job (although this was the same character who convinced us all that it’s impossible to lose much on a two-year bond and there was no way the Danes would reject the Maastricht Treaty).

I am thankful I had nearly 40 years of doing a job I loved, working with fantastic colleagues, supportive clients and entertaining competitors. For all the changes, the market still has risk-takers, great (and funny) characters and mostly learns from its mistakes – and still produces great stories that would not be fit for publication in IFR.

Chris Tuffey worked at Credit Suisse until 2023, his only employer during a 37-year career in the financial markets. He ran debt syndicate and EM capital markets in London following time in New York, Hong Kong and Tokyo.

To see the digital version of this report, please click here

To purchase printed copies or a PDF of this report, please email shahid.hamid@lseg.com in Asia Pacific & Middle East and leonie.welss@lseg.com for Europe & Americas.