ECM: spring of hope, winter of despair

Former ECM banker and self-described origination junkie Craig Coben looks back on the good times, bemoans the present and manages – just about – to be hopeful about the future.

Right now, it’s hard to muster much optimism about the future of equity capital markets. Issuance volumes have crashed; liquidity has dried up; the pool of long-only investors has been drained out; and the IPO market has transmogrified from a forum for fresh fundraising into a dumping ground for exiting insiders.

Today stands in stark contrast to the jaunty optimism that prevailed when I started in the late 1990s. The UK stock market, like Britpop, reigned supreme, while Continental Europe embarked on a series of jumbo privatisations, energising their somnambulant stock exchanges and attempting to create a path to a mass equity culture.

Those were heady days. European banks rivalled their American counterparts. When I started at Deutsche Morgan Grenfell in 1997, SBC Warburg, CS First Boston, ING Barings, Dresdner Kleinwort and the old UBS were formidable players in EMEA ECM. Even after shakeouts and consolidation, Deutsche Bank and (post-merger) UBS emerged as two of the strongest EMEA ECM houses, and Credit Suisse was no slouch either. And investors everywhere wanted to support our deals. We were roadshowing companies in The Netherlands, Scotland, Ireland and Switzerland, as well as the usual venues of London, New York, Paris, and Frankfurt.

For a while it was exhilarating to visit Europe’s great cities, work on massive privatisations, and sit at the epicentre of multi-billion US dollar fundraising. Sometimes it was crazy. I remember working in 2000 on the IPO of EADS (now Airbus) and for political reasons we had to have a meeting every week in each of Munich, Paris and Madrid to reflect the different shareholders coming together. Back then we had mobile phones but no Blackberries, and the constant movement complicated the day-to-day execution. We also held three listing ceremonies at three different stock exchanges. Even then I wondered if this cumbersome arrangement was a parable of European integration and cooperation – or a cautionary tale.

Buoyantly bullish

Anyhow, as I said, we were buoyantly bullish on Europe then. I remember one excitable Italian managing director talking breathlessly in the late 1990s about launching a PERO – pan-European retail offering – “from Lisbon to Luebeck”. It speaks volumes that such a vision seemed entirely credible then but today sounds quixotically risible.

The good vibrations just didn’t last. The TMT bubble burst in 2000, and the titans of European life insurance teetered on the brink of collapse due to their over-exposure to the equity market. Round after round of layoffs ground down morale during 2001–2003. It was a dispiriting time. I was catching the 6am Heathrow flight to Milan or Madrid and pitching for business that I knew had a low chance of materialising. When my boss told me what my 2002 bonus would be, it wasn’t quite a doughnut, but I remember his words: “I know you’re unhappy but at least you still have a job … unless I change my mind.”

Borrowed time

Like Austin Powers, Europe’s equity capital markets had lost their mojo, and despite periodic market recoveries, I’m not sure they ever fully regained it. We had good years – the mini-bubble of 2006–07, the humongous rescue rights issues of 2009, the surge of optimism around UK IPOs in 2014, and of course the Covid-driven tech frenzy of 2020–2021.

But the primary markets in Europe never really took off sustainably, and there was always the feeling that you were living on borrowed time. Every time they seemed to come back, something would come along to spoil the party: the 2008 financial crisis, the Eurozone crisis in 2011–12, the taper tantrum of 2013, the Brexit referendum in 2016, and the crash in tech and assorted “concept” stocks in late 2021.

We barely realised it at the time, but while we were talking up ECM with our PowerPoint presentations, European equity markets were starting to wither away. The causes are multiple: Solvency II, ill-designed pension reforms, MiFID II, Brexit, ZIRP, slow economic growth, hobbled banks, cultural norms of risk aversion, emergence of private pools of capital. European equity markets have now been relegated to junior varsity status: on-market liquidity has dwindled, and the centre of gravity has shifted (depending on one’s perspective) to private equity or to the US.

The impact has reverberated through ECM on multiple dimensions. Roadshows don’t bother with investors outside a few financial centres. The vaunted “UK Club” of supposedly long-term investors has been supplanted by a handful of global, US-headquartered mutual fund complexes and maybe the odd sovereign wealth fund. If you don’t have one of this small number of Big Kahunas in your IPO, you don’t have a long-only book to allocate.

Meanwhile, the sales forces have lost their status. When I started, we had Big Beasts in equities sales – wise and wizened figures who jealously guarded access to portfolio managers. I was so flattered when one of them invited me (as the sole ECM attendee) to his birthday party at a private club in the late 1990s; his friends and hangers-on were as stylishly good-looking as they were achingly cool.

That’s from a bygone area. Electronification has eroded the role of high-touch cash equities, and compliance restrictions have curtailed a salesperson’s ability to communicate with investors beyond a sanitised message. Also, the increased reliance on long/short hedge funds (aka “liquidity providers”) has meant ECM offerings are mostly distributed from the syndicate desk. With salespeople marginalised, the heads of syndicate have now become the “Number 10” on the ECM pitch: everything flows through them, and they set the pace and cadence for origination, allocation and even risk commitment.

Another noticeable development has been the eclipse of the European banks in ECM. The Americans now dominate EMEA ECM, largely because they had stronger global profitability and avoided the risk landmines that the European banks stepped into. Deutsche shut down much of its equities business, UBS pulled back from chasing league table glory, and Credit Suisse collapsed after a bank run. Deutsche and UBS are staging recoveries, BNP Paribas has made strides, Barclays has built a strong UK franchise and HSBC won IFR's 2022 EMEA Equity House of the Year after a strong showing. But overall the withdrawal of the bulge-bracket Europeans has translated by default into sizeable market share gains for the US banks.

While ECM may be marginally less competitive today, it has become materially more commoditised, with underwriters struggling to differentiate themselves. Everyone courts the same investors who in turn often don’t care who the underwriter is. The mandated bank is often the institution that commits the most balance sheet or did some other kind of favour for the corporate or vendor.

Bitter pill

This development has been a bitter pill for originators. Every ECM originator likes to believe (perhaps out of vanity) that they could win a pitch through a high-octane cocktail of analytic rigour and force of personality. I used to think it was down to me to win the deal, and I relished the challenge.

And this made ECM fun. Every victory was savoured, and I learned to shrug off even the most soul-crushing losses. I was a proud Citizen of Nowhere in my work: global and globalised, working with and for a multicultural mix of nationalities, speaking different languages (sometimes well, sometimes butchering every word), travelling seamlessly across borders, ready to be parachuted into any situation in strange and sometimes hostile territory. It wasn’t intellectual, but it was mentally stimulating and emotionally rousing.

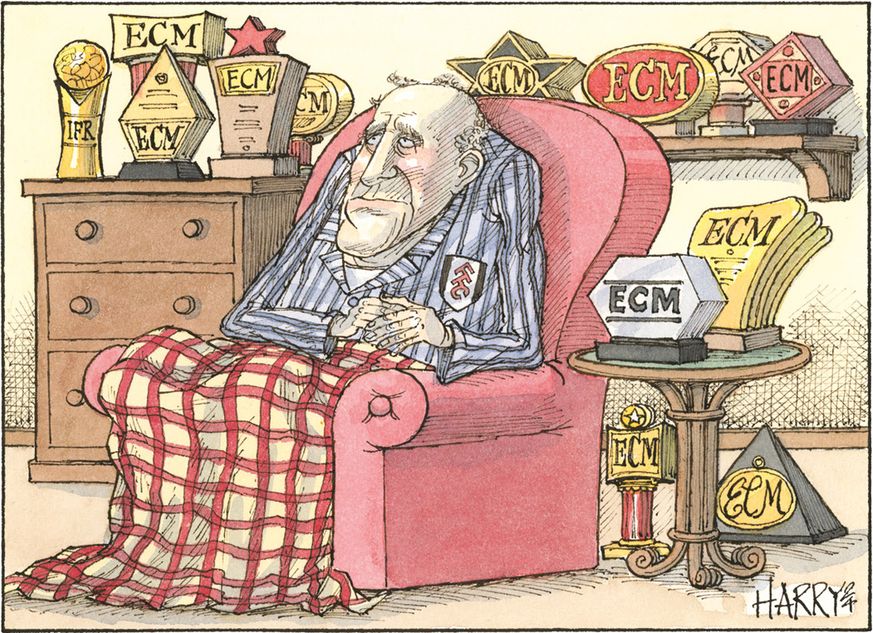

In short, I was an origination junkie, and after nearly two years of retirement, I’m still suffering withdrawal symptoms. My column-writing punditry has been my therapy.

I have some incredible stories about trips to isolated places, brilliant feats of improvisation, and amazing comebacks. But as my fellow New Jersey native Tony Soprano says: “‘Remember when’ is the lowest form of conversation.” Nostalgia is a dead-end. The stories are interesting for me, but probably not for you. Besides, I’m told IFR is a family-appropriate magazine.

Waking up

So time to look forward. It’s just about possible to be optimistic even as ECM revenue hits new lows. Higher interest rates will make it harder for firms to raise capital privately. The stock market will return to its original purpose as a venue for raising money for investment, expansion and acquisition. And I know from my own discussions that governments across Europe are waking up to the damage that their often well-intentioned policies have wrought, as well as to the public interest in a robust equity market.

When ECM volumes come back, its champions have the chance to turn that recovery into a lasting renaissance. ECM matters in a way that few areas of finance do, and I will miss not being part of the action. Give me a call sometime, ok?

Craig Coben worked at Bank of America (originally Merrill Lynch) from 2005 until 2022, serving in a variety of senior roles, including global head of equity capital markets and vice-chair of global capital markets. He had previously spent eight years in the equity capital markets team at Deutsche Bank. He is now a managing director at SEDA Experts.

To see the digital version of this report, please click here

To purchase printed copies or a PDF of this report, please email shahid.hamid@lseg.com in Asia Pacific & Middle East and leonie.welss@lseg.com for Europe & Americas.