Chinese banks go global – slowly

PRC institutions take lion’s share of Asian investment banking fees, and are steadily expanding into overseas markets.

Chinese banks have prospered over the past two decades as onshore capital markets have developed and Chinese issuers have, until recently, dominated offshore issuance in Asia.

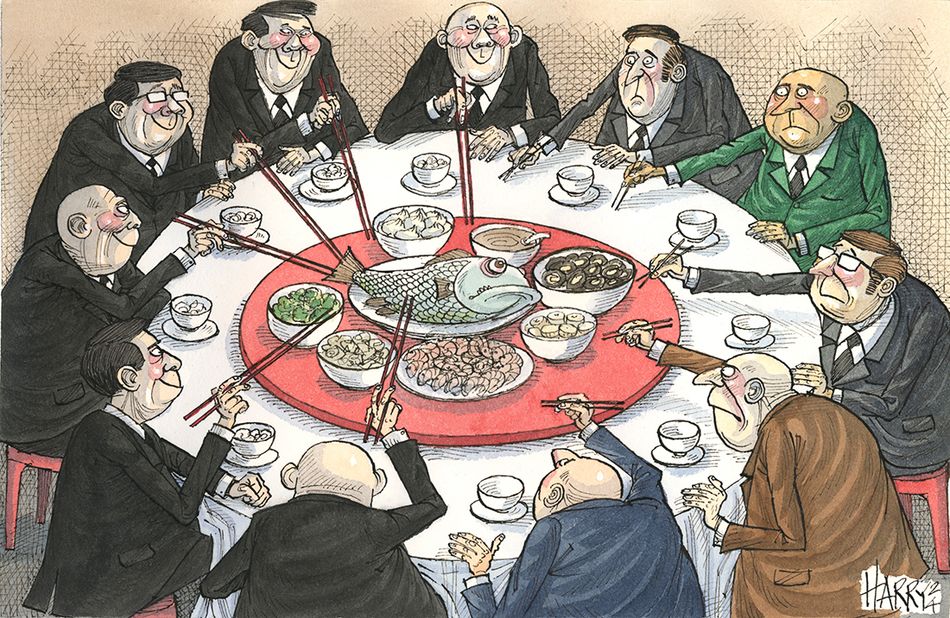

That has prompted many to ask whether Chinese investment banks can start eating into global houses’ wallet share internationally – or whether they even want to.

Certainly, Chinese banks are leading the way in fee income in the Asia Pacific ex-Japan region.

Ten years ago, Citic was the only Chinese bank in the top 10 league table for investment banking fees in Asia Pacific ex-Japan, according to LSEG data. In 2023, the top 10 was entirely Chinese.

In part that reflects the slowdown in deal activity across the region and the dearth of offshore deals from China. But Chinese arrangers have seen their fee take and wallet share increase dramatically over the past decade.

In 2013, Citic earned US$283m in fees for a 2.7% market share. In 2023, that had rocketed to US$1.8bn and a market share of 6.4%.

Bank of China, China Securities and CICC earned US$1.8bn, US$1bn and US$865m in fees, respectively. By comparison, the top non-Chinese bank was HSBC, which brought in US$471m in 2023 for a 1.7% market share, compared with fees of US$411m and a 3.9% market share in 2013.

Chinese banks have made significant headway in investment banking, even as profits have shrunk at home amid headwinds from lower lending rates and a property sector crisis. These banks also remain outliers in regional investment banking because they have made barely any layoffs, while their western counterparts in the region have shed dealmakers. In fact, recruiters in Hong Kong say Chinese banks are among the only ones hiring in investment banking at the moment.

Expansion mode

Some are expecting Chinese houses to build on this success to expand into new markets. They have already turned up on some far-flung deals – ICBC has worked on US dollar bond offerings for Angola, for example, while a Bank of China unit was a bookrunner on Saudi Aramco’s IPO.

“[Chinese banks] have been expanding overseas. In most of these markets, their role is not to compete directly with incumbent banks, but mostly to bank existing mainland customers that are also expanding abroad,” said Grace Wu, head of Greater China banks at Fitch. “Their strategy tends to be quite selective.”

Citic Securities, for instance, operates in 13 countries. Citic, which already has an office in London, is opening an office in Germany and one in the Middle East in the coming months. In South-East Asia, the bank has a presence in Singapore, Malaysia, Indonesia, the Philippines and Thailand.

“There are also some subsidiary investments along the Belt and Road countries, funding some of those initiatives,” Wu said. Altyn Bank, a subsidiary of Citic, in Almaty, Kazakhstan is one such example.

CICC has over 200 branches in the Chinese mainland and offices in Hong Kong, Singapore, Tokyo, New York, San Francisco, Frankfurt and London.

“We are committed to Asia and growing here,” said Bagrin Angelov, head of cross-border M&A with CICC’s investment banking arm. “We have the willingness to expand in the region – Singapore, Japan, et cetera – and there are others in the works.”

Banks are taking different approaches to expansion, with some forming regional headquarters while others collaborate with local branches, Terence Fong, head of Chinese banks at KPMG China in Hong Kong, wrote in a note. Some Chinese banks are also actively looking at other locations further afield, including countries in the Middle East and Central Asia that are part of the Belt and Road Initiative.

“Hong Kong also serves as a training hub for talent for the Chinese banks’ overseas operations as part of these plans to expand internationally,” Fong wrote.

Among the other Chinese houses, Haitong has a presence in Sao Paulo, London, Paris, Lisbon, Madrid and Warsaw, besides Shanghai and Hong Kong. ICBC has a wide presence in Asia and the Middle East, Europe, North America as well as Australia and New Zealand.

Citic, Bank of China, Haitong, and ICBC did not respond to emails seeking comment.

“Outside of China, these banks are interested in every country with the potential to grow,” an analyst covering investment banking in Asia said. “Moving out of China is easier if they target South-East Asia. They cannot really compete with Citadel or Natixis in Europe or Mizuho or MUFG in Japan.”

South-East Asia and beyond

Mainland banks began to venture into South-East Asia because the Chinese diaspora in the region increasingly wanted to remit money back to China. Eventually, that turned to overseas clients wanting access to domestic capital markets and domestic customers wanting access to overseas markets.

“When people engage a Chinese bank in South-East Asia, they are not engaging them for the bank or the bankers – they’re engaging them for the access to investors and Chinese money,” said a Hong Kong-based investment banker.

Chinese banks’ international investment banking business mainly involved facilitating capital moving out of China, but that is not happening right now, said another Hong Kong-based banker with a global bank.

Bankers in Asia have said that the future of China dealmaking hinges on money from the Middle East. Mubadala, Abu Dhabi’s sovereign wealth fund, said in December that its investment focus is shifting towards Asia, with less emphasis on the United States and Europe.

Some Chinese banks like CICC are going to the Middle East to look for capital, the second Hong Kong-based banker said.

Outside opportunities

“Chinese banks also have a good opportunity to leverage opportunities arising from Credit Suisse’s exit from Asia,” the investment banking analyst said.

Credit Suisse had a big presence in markets like Indonesia and India, but UBS has slashed headcount following the acquisition of its Swiss rival last year and is expected to take a more conservative approach to risk.

“A lot of Credit Suisse’s business in Asia was seen as very risky. Maybe local banks would step up, maybe boutiques, but certainly not the international banks,” the first Hong Kong-based investment banker said. “Chinese banks might, depending on their risk appetite.”

Fitch’s Wu expects Chinese banks to be opportunistic when it comes to Credit Suisse’s wealth management business, but in investment banking she expects caution. “If they don’t have existing expertise, they won’t necessarily be aggressive in these areas,” she said. “State-owned banks tend to be quite conservative relative to smaller banks in China.”

Chinese venture capital companies moving into South-East Asia to target start-ups in the region also present an opportunity.

“Chinese private equity funds are opening up a presence in Singapore and elsewhere,” a Singapore-based investment banker said. “These are the opportunities Chinese banks will want to pursue.”

Shunwei Capital, a private equity fund founded by Tuck Lye Koh and Xiaomi founder Lei Jun, registered a Singapore affiliate named SWC Global in 2020. Source Code Capital, an investor in Chinese technology giants like ByteDance and Meituan, is also said to be building a presence in Singapore.

One country Chinese banks are unlikely to wade into is India. Despite an investment banking boom in Asia’s third-largest economy, government restrictions and geopolitics will likely deter mainland banks.

Potential roadblocks

A potential roadblock for mainland banks venturing outside of China is the country’s own regulatory restrictions.

“It is natural for regulators to be mindful of risks as these banks expand outside their scope. Any regulator has good reason to monitor the pace of expansion outside their home jurisdiction,” Wu said.

In October, the China Securities Regulatory Commission asked Chinese brokerages and their offshore units to close new account opening channels for domestic investors seeking to invest in overseas markets. The CSRC note also asked brokers to stop marketing these services to investors at home and abroad.

Bankers and analysts pointed out other challenges Chinese banks are likely to face outside their home markets.

“It is not going to be easy. Banks have been trying to go out of China for years – CICC, Haitong, Huatai – but issues come up for them like for any other bank expanding outside their local market. Getting clients, licences, understanding the local market,” said an investment banker with a foreign bank in Greater China.

“Access to local currency funding presents a funding challenge for Chinese banks looking to expand outside of China and attracting and retaining talent to compete with incumbent banks could also be a challenge,” Wu said.

Venturing into a new market independently is also not easy.

“No doubt some of these banks are looking to expand beyond their home market – especially the large Chinese banks want to do more overseas – but they may not be entirely comfortable doing it alone,” the banker with the foreign bank said. “Partnering with someone that has the know-how and experience to navigate local regulations and culture makes sense.”

Citic has seen success in markets like Indonesia after acquiring CLSA in 2013, making it the first Chinese brokerage to buy a global financial institution.

Still, despite challenges, bankers agree that there are multiple pathways emerging between China and the Middle East, Latin America, Europe and Africa. “There are flows to be captured,” the Singapore-based investment banker said.

“The question with these expansions overseas is, will it stick?” the first Hong Kong-based investment banker said.

To see the digital version of this report, please click here

To purchase printed copies or a PDF, please email shahid.hamid@lseg.com