M&A Deal: UBS’s SFr3bn acquisition of Credit Suisse

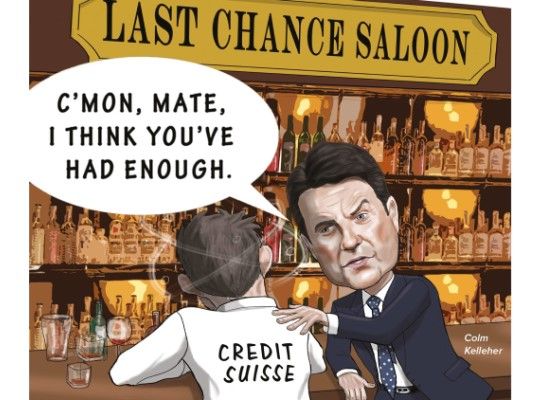

Calling time

UBS had long considered a takeover of Credit Suisse, to create a US$5trn national champion, a remote possibility but that idle dream turned into an initially uncomfortable reality when an old-fashioned bank run meant Credit Suisse – and Switzerland – needed a saviour. UBS’s acquisition of Credit Suisse is IFR’s M&A Deal of the Year.

There is no getting around the fact that UBS’s acquisition of Credit Suisse for just SFr3bn (US$3.3bn) announced on Sunday, March 19 was the most significant M&A deal of 2023.

If it hadn’t happened, and a global systemically important bank had been put into resolution, global markets and the wider economy would have been in a far darker place with the ensuing uncertainty such a decision would have sparked.

Even at the start of the year, after Credit Suisse had already seen significant deposits flee after a social media post in October suggested a GSIB was in trouble, the Swiss authorities had decided that the best outcome would be if UBS stepped in and took over its arch-rival.

UBS was also ready on January 1, if it was ever asked, to carry out this mandate, after the previous quarter’s high profile liquidity problems for Credit Suisse. And it had already lined up Morgan Stanley to help it, if needed.

“There was no way out, other than Credit Suisse being taken over by somebody,” Colm Kelleher, chairman of UBS since the previous April, told IFR.

At that stage, for those outside the corridors of power in Switzerland, there was a possibility that other institutions, such as Deutsche Bank, could have stepped in and effectively broken up the bank by selling off the domestic lender and wealth manager.

Credit Suisse itself, with help from Centerview Partners, was pressing on with its plans to sell its securitised products business to Apollo among other elements of its strategic plan, and still intended to avert a rescue intervention. Deposit outflows had stabilised too.

That reasonably calm start to the year changed in early March, on severe market fluctuations which led to the US authorities stepping in to wind down Silicon Valley Bank and Signature Bank after losses on their bond portfolios had sparked runs by their uninsured corporate depositors.

The day after the US Federal Deposit Insurance Corp’s intervention on Monday, March 13, the situation at Credit Suisse was reasonably stable, but the idea of Deutsche Bank or any other non-domestic party coming in – probably already a non-starter – was definitely off the table in such febrile financial markets.

After major shareholder Saudi National Bank publicly rejected the idea on the morning of Wednesday, March 15 that it might provide more capital to Credit Suisse, a major sell-off of the lender’s securities ensued. At one stage its Additional Tier 1 notes were trading at just 23% of par.

Kelleher was due to have a regular meeting with Swiss regulator Finma that afternoon. In the end he was asked to bring other senior colleagues to meet an array of regulatory officials, headed by Swiss finance minister Karin Keller-Sutter and Swiss National Bank chairman Thomas Jordan.

They told the UBS delegation that Credit Suisse was no longer viable and that they favoured a takeover by UBS – if not, the failing lender would be put into resolution that weekend. SFr50bn of emergency liquidity would be provided by the SNB, with possibly more to follow.

Kelleher was not altogether surprised but made clear it was not a simple deal. “I was clear that we were prepared to take them over but with our minimum terms. And by the way, they were not negotiable because I had a duty to my shareholders as well. A fiduciary duty," he said.

With only four days to conclude the agreement, UBS could do little but look at what was legally disclosable: the mark-to-market value of the assets on Credit Suisse's books and what other contingent liabilities might arise.

The question over what might happen to Credit Suisse’s domestic business and branches, which employed many people, was another factor overshadowing the swift negotiations. UBS did not want to be bound by any conditions regarding where the obvious synergies were.

“So then we got into due diligence. It got very intense; a lot of calming people down," said Kelleher.

Hired help

Both sides brought in other banks to help at this stage: JP Morgan for UBS and Rothschild for Credit Suisse to provide a third-party view.

Morgan Stanley provided UBS with most help. “I knew the team. I trusted them implicitly. I knew they had FIG specialisation. I knew that they would bring value and see the things I wouldn't see. They did that classic M&A job of joining up the dots,” said Kelleher.

The Morgan Stanley bankers were ready and waiting. “This was a situation we had prepared for as adviser to UBS for some time,” said Jan Weber, head of M&A for Europe, the Middle East and Africa at Morgan Stanley. “Even perfect plans do not survive contact with reality and that was certainly the case over that long weekend.”

By Sunday morning the die was cast as the two parties met the authorities, first Credit Suisse then UBS, to finalise the agreed terms.

The broad structure of the deal had been determined. Credit Suisse’s SFr16bn of AT1 notes would be wiped out and UBS would pay a nominal sum for the bank’s equity.

UBS was originally only going to pay SFr1bn and be provided with around SFr5bn of insurance by the state against possible future losses. In the end Credit Suisse was taken over for SFr3bn and SFr9bn of potential losses covered.

The press conference with Keller-Sutter, the regulators and the two banks’ chairmen started at 6:30pm CET, after severe pressure during the rest of the day from governments around the world to get the deal done before the markets opened on Monday.

“This is no bailout. This is a commercial solution,” Keller-Sutter said at the time.

Kelleher was still worried about the next steps. “My biggest concern was contamination risk. There was no guarantee that we would announce a deal that the market would like,” he said.

This was a legitimate fear. On Monday morning UBS shares opened down 17% before recovering.

“From a bank rescue perspective, the question was ‘will this hold on Monday morning?’. How would shareholders react? Will there be an AT1 market in Switzerland again? In hindsight it now looks fine but at the time it was critical for the UBS board making those decisions,” said Weber.

If Kelleher had not been satisfied that sufficient safeguards were in place the deal might not have got over the line.

“I would have walked away if we didn't get certain conditions. But the bar for walking away was very high. But the reason we would have walked away is the contamination risk for UBS was huge. If we didn't get safeguards, we would have walked.”

Walking away would have been a monumental call, since that would have been bad for the whole system.

“We felt that UBS buying Credit Suisse was clearly better than resolution. But what we couldn't do is have UBS getting into a position where it suddenly became the target,” he said.

That had happened in September 2008 when the implications of Lehman Brothers filing for bankruptcy questioned the viability of other major banks. This time around such an outcome was averted.

Asked who was the driving force behind the deal, Kelleher said: “It was a UBS deal and a Swiss Inc deal.”

To see the digital version of this report, please click here

To purchase printed copies or a PDF of this report, please email shahid.hamid@lseg.com in Asia Pacific & Middle East and leonie.welss@lseg.com for Europe & Americas.