SSAR Issuer: World Bank

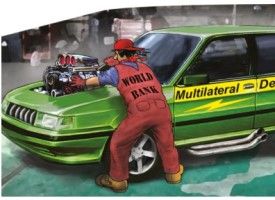

Souping up MDBs

As calls grew for multilateral development banks to expand their lending to help the world adapt to climate change and all the challenges it brings, the World Bank has been at the forefront of efforts to evolve the model MDBs use to effect change. The World Bank is IFR’s SSAR Issuer of the Year.

On top of delivering the usual funding in what seem to have become perennially uncertain markets, the World Bank has led the way in revising what shape funding and lending from multilateral development banks should take as the world confronts climate change.

Those efforts came as part of a US$49bn funding spree over 220 transactions the supranational did across 22 currencies in 2023, according to the World Bank’s head of funding Andrea Dore.

Among the most high profile of its efforts is the hybrid bond project the World Bank undertook to increase its capital base and hence how much it can lend by multiple times the original bond’s nominal size.

“The effect [of hybrid deals] is to increase the equity, and by increasing the equity it allows us to be able to [lend] more,” Dore said.

Its €305m hybrid private placement in September formed a large part of that push. The unprecedented transaction agreed with shareholder Germany marked the World Bank’s response to increasingly urgent calls for multilateral development banks to expand their lending and help developing countries transition to green energy and adapt to the effects of climate change.

The deal also set a precedent for how MDBs handle hybrid issuance. Other member-states and non-shareholder buyers are thought to be lining up to buy more World Bank hybrids.

But hybrid instruments are only among the more high-profile projects the World Bank is working on to boost MDBs’ impact. It has also taken a leading position in proposing portfolio securitisation as another way of expanding MDBs’ lending without the sometimes politically uncertain process of securing more paid-in capital from shareholder nations.

Speaking at the COP28 climate meeting in Dubai, World Bank president Ajay Banga said a key goal would be “figuring out a model of originating to distribute, of creating a securitisable asset class … where large pension funds [and] large players like BlackRock would find that to be an attractive place to put billions to work”.

So far, there have been some securitisation projects among MDBs, but nothing that has been scalable.

Projects to structurally soup up its funding and lending at a macro level have not distracted the World Bank from its goal of reaching people at the front line of its work to relieve poverty.

Among the hundreds of transactions the World Bank did in 2023, Dore gave the example of the US$50m emission reduction-linked bond in February, which provided upfront financing for a water purification project in Vietnam.

The five-year bond sale was linked to the issuance of verified carbon units produced by the project. It aimed to make clean water available to around two million children and avoid almost three million tonnes of CO2 emissions over five years.

“The size does not really give the true story of impact: we were able to distribute 300,000 water purifiers across 1,000 schools and [other] institutions,” Dore said. “So the impact is significant.”

The structure is designed to give investors confidence about the dual impact of the bond: both a social impact in improving access to clean water, but also showing a quantifiable reduction in carbon emissions via carbon credits.

The World Bank’s impact is not limited to addressing problems that already exist. It is also active in preparing for catastrophes that are yet to come via its US$6bn catastrophe bond and swap programme.

In a deal announced in March, the World Bank generated US$630m of insurance cover for Chile against earthquakes and tsunamis with its largest single-country transaction yet: US$350m of three-year catastrophe bonds and US$280m of catastrophe swaps.

“How do you manage [a catastrophe] to lessen the impact on the country? By allowing them to access funds very quickly,” Dore said.

Doing the bonds and the projects is one thing, but the World Bank also wants to pass on its lessons from those projects, Dore said, citing a call with a number of regulators about climate bonds as well as one on using blockchain to improve knowledge about those areas.

To see the digital version of this report, please click here

To purchase printed copies or a PDF of this report, please email shahid.hamid@lseg.com in Asia Pacific & Middle East and leonie.welss@lseg.com for Europe & Americas.