If 19th century philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche was surveying modern finance, he might well say “IPOs are dead. IPOs remain dead. And we have killed them!”

So far in 2023 there have been 60 IPOs in the high-margin US market raising US$11.6bn, according to LSEG data. That is roughly a quarter of the average raised annually in the past decade – from well under half the average number of listings. The picture in Europe is equally bleak. Here, IPO activity is shaping up to be the second slowest year in the last 10 years, behind only 2022’s exceptional slump, with companies raising about US$15.5bn – just over a third of the annual run rate in recent times.

Here's the thing: The outlook for 2024 is cloudy owing to the poor performance of recent IPOs and low valuations of publicly listed peers. And yet banks have kept their expensive equity capital markets desks largely intact through the downturn, not wanting to miss any strong rebound. Inevitably, something has got to give.

There are several good reasons to think the picture won’t improve next year. For all the negative attention European bourses have received, recent IPOs in the US have also struggled. The post-Labor Day deal flurry was priced too richly and fared poorly.

ARM Holdings is up slightly since SoftBank listed the British chip designer, but it is a unique beast given its extremely long and well-established track record in its industry and with investors. Potential technology IPOs for 2024 are more likely to look like decade-old Instacart, which trades about 15% below its IPO price.

Venture capital-backed tech unicorns like Databricks will be hoping that the recent stock market rally continues and broadens out beyond the “Magnificent Seven” tech stocks of Alphabet, Amazon, Apple, Meta Platforms, Microsoft, Nvidia and Tesla. Artificial intelligence has been a massive tailwind for these mega-cap tech firms, but most of the smaller generative AI companies are still in VC funding mode. The sector that was the obvious candidate to drive IPO activity was fintech payments and neo banks. However, the collapse of valuations of listed lenders and payments firms will make deals difficult for the likes of Stripe, Checkout.com, Revolut and Starling.

The private equity pipeline doesn’t look much better. Last month EQT boss Christian Sinding said there’s “dysfunction” in the IPO market and said the private equity giant was testing the idea of private stock sales of its portfolio companies to existing investors. The plan was met with a degree of scorn on the assumption it was an excuse to dodge properly having to mark assets to market. And there is no doubt that deal volumes and exit activity have slowed in private markets, which will also be tougher than in the last decade.

Better shape

Nevertheless, financial sponsors are in much better shape than active public equity investors, complete with lots of dry powder waiting to be deployed, healthy fundraising rounds under their belts and large private credit businesses to sustain them. All this could mean a trend of more sponsor-backed companies avoiding the IPO route.

High-profile share price collapses of private equity-backed IPOs – whether it be the slow burn of a Bumble, or the implosion of CAB Payments – will also make public market investors cautious about taking the other side to sponsors selling large chunks of companies at IPO or soon after.

From the private market investor perspective, meanwhile, the thin free-floats of recent deals leave a lot of risk on the table. It may be better to sell the whole business to another sponsor or to a large, publicly listed corporate that is flush with cash. Private ownership is not a silver bullet in itself, but it does give a lot more room for manoeuvre, while no public market investor wants to see a newly listed company warn on profits and need restructuring. On a more abstract level, an IPO is no longer seen as the prestige event it was in terms of giving companies credibility with customers and other stakeholders.

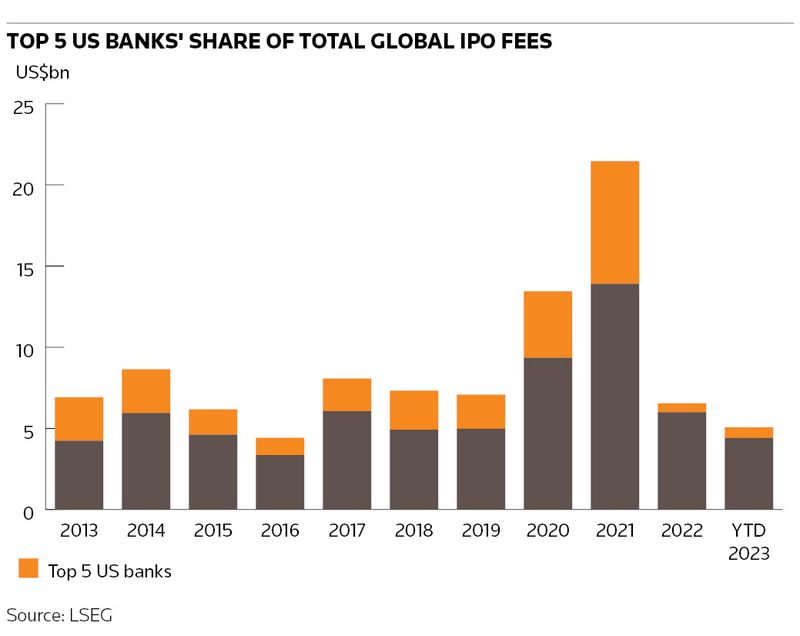

So where does this leave banks’ ECM desks? IPOs remain a core part of the overall package of services that investment banks offer. But LSEG data shows that banks have generated only US$5bn in fees from IPOs in 2023 and US$6.5bn for the whole of 2022. That is just 5% of total investment banking fees, and the Chinese banks that dominate their home market are the largest part of this. The top five US banks in aggregate have only generated about US$650m in fees from IPOs this year, barely better than US$550m in 2022, but still well below the US$2.7bn average of the past decade.

Bankers will say there’s a “glass-half-full” outlook for the IPO market, where sentiment remains king. The giant fast fashion retailer Shein has just filed with US regulators for an IPO that could take place next year and will be a litmus test for China-linked firms. Then there are more traditional US tech names like social media firm Reddit and data security firm Rubrik. In Europe, Italian luxury sports shoe brand Golden Goose is lining up to list in the first half of 2024. And there are even rumours of the Kim Kardashian-backed Skims underwear label considering the IPO route.

Expensive business

But that doesn’t alter the fact that IPOs are an expensive business for banks. Lead times are long and the underwriting process requires a lot of people. That’s not just the army of underlings needed to support senior dealmakers. Banks must also cover the overheads of large cash equity sales and research desks, which typically struggle to generate secondary commissions.

In short, banks’ ECM desks face a day of reckoning. Between the shrinking IPO pie, fierce competition and margin pressure if sponsor business slows permanently, ECM desks will have no choice but to examine their cost bases and how they organise teams. And if ECM isn’t bringing in the fees that pay for expensive equity sales and research platforms, then they must be at risk too. Because, as things stand, the numbers just don’t stack up.

Rupak Ghose is a former financials research analyst