Citigroup’s Canary Wharf tower is currently a building site, a belt of scaffolding hanging round its waist, as the US lender renovates the floors that house its traders and other bankers.

Andrew Morton, Citi's head of markets, has been facing a similar task: to revamp the bank’s trading unit to make it more profitable, while strengthening the pillars that have made it Citi’s main revenue generator and one of the world’s largest markets businesses.

“We’d rather have better returns than win in some [revenue] ranking contest,” Morton told IFR. “We’re in a different position to other firms. We have tried very hard to be efficient with our capital footprint to reflect Citi’s overall goals.”

Morton keeps a low profile considering his reputation as one of the most successful traders of his generation. But he has been thrust into the limelight following chief executive Jane Fraser's decision to strip away a layer of senior management in a move that coincided with (or perhaps resulted in) the retirement of investment bank head Paco Ybarra. That put Morton just one rung below the top job, reporting directly to Fraser, as she looks to get a firmer grip on the bank’s sprawling operations and boost Citi’s sagging share price.

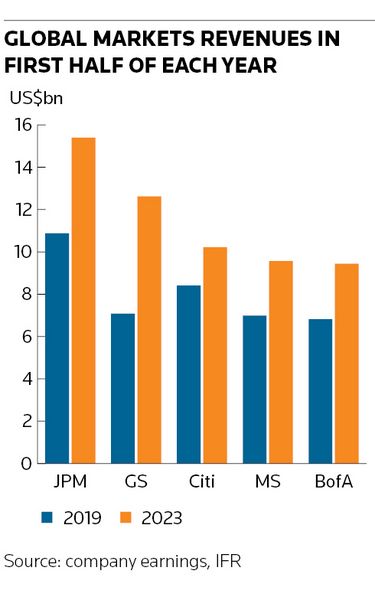

Citi is the third-largest bank in sales and trading, its revenues providing a substantial layer of ballast to the wider firm that has helped offset recent declines in businesses such as investment banking. Global markets, where Citi helps its corporate and institutional clients trade everything from US Treasury bonds to commodities, stock options and emerging market currencies, has grown 22% in the past four years to account for a quarter of the bank’s US$41bn first-half revenues – more than any other division.

But the growth of recent years hasn't been enough to dispel concerns over the large sums of capital Citi’s trading desks consume and the consequent drag on shareholder returns. Increasing the profitability of the markets division was an important part of the new strategy that senior management announced 18 months ago – and the bank has lost no time in reshaping the business.

“The capital that’s attached to markets businesses is very high,” said Morton. “We have a scale business that brings in a lot of revenue. That’s why we don’t need to take outsized risks. [But] we do have to manage the costs and the capital.”

Citi has taken a two-pronged approach to reinvigorating its markets unit: shrinking low-returning activities – for example, trading bank loans or FX forwards – while investing in areas it thinks offer better returns. That includes fleshing out its stock-trading division to bring greater balance to a markets business that has long been defined by its prowess in trading bonds and currencies.

Citi's fixed-income unit is second only to JP Morgan’s in terms of heft, with its position in macro products linked to interest rates and currencies coming to the fore when dramatic shifts in central bank policy have dominated markets. But the bank remains a relative minnow in equities next to its Wall Street rivals even after expanding considerably in recent years, something that limits its ability to capture a revenue upswing in those markets.

“You have to be able to reinvest,” said Morton, reeling off a string of priorities including physical commodities trading and financing, European government bonds and equity prime brokerage. “But to do all that we have to downsize somewhere else. We view it as a churn: winding down any business that is not as return accretive, or not as important to clients any more.”

From maths to markets

Morton’s path to becoming Citi’s top trader started in academia, where he helped develop a widely used mathematical framework for valuing derivatives. He joined Lehman Brothers in the 1990s as a quantitative analyst and, after getting his break in trading, rose through the ranks to become global head of fixed income. Morton moved to Citi in 2008 shortly after Lehman’s collapse and spent the next decade building the bank’s rates trading business.

He credits his background for his analytical approach – and his appreciation of some of the bank’s less glamorous operations. “The best traders are not sitting there calling the market: they’re with their tech and quant partners trying to build a better tech risk-management system,” he said.

So what does he make of the artificial intelligence boom? “There’s going to be more efficiency, but we’re not going to have traders trading on AI.”

It is perhaps telling that Morton, as a veteran fixed-income trader, becomes most animated when outlining Citi’s plans for equities. A successful push in equity derivatives has helped Citi grow its stock trading division in recent years, but the bank still lags “miles behind”, in his words, in prime brokerage even after increasing prime balances by about 40% since 2019.

Financing hedge funds’ stock portfolios generates a huge portion of the earnings at the largest equities firms, providing a sticky, recurring revenue stream. Morton and Fraser have been on a charm offensive with clients to drum up more of this business, though he concedes it could take years to bear fruit.

"We have the ingredients – the technology and the client relationships – to build that business," said Morton. "It’s important to invest in permanent, rather than short-term, gains. If we double our prime balances, that’ll be a permanent gain that no one will take from us."

He drew a comparison with how Citi has built its commodities business “from scratch” over the past 12 years into one of the largest offerings around. “It’s better to do these things right and take 10 years rather than rush,” he said.

Long-term gains

One challenge is that cost-cutting measures tend to bite before the rewards of longer-term investments kick in. Citi has, for instance, hacked back credit trading, where it buys and sells corporate bonds and related products. The stage of the credit cycle, with depressed dealmaking volumes, hasn’t helped these activities, but there's also been a conscious decision to shrink capital-intensive areas like loan trading.

“We’ve tried to rationalise [the credit trading] business. We lost some people, and we got out of a few products," said Morton. "But in investment-grade credit and structured products we’re still there – the noise is worse than the reality.”

Such decisions have contributed to a decline in Citi’s share of the industry revenue pool in global markets in recent years – even as its business has grown in absolute terms. Fiercer competition has also played a role.

Goldman Sachs has expanded rapidly to displace Citi as the second-biggest bank in sales and trading behind long-time leader JP Morgan, while Morgan Stanley and Bank of America have also made up ground. Elsewhere, Barclays, BNP Paribas and Deutsche Bank have all ploughed resources into their trading units – a contrast to much of the previous decade when many European lenders were in retreat.

“Many people are getting back into the game. Sometimes they lead with price, sometimes they hire your talent,” Morton said. “Our approach is to be consistent with clients and offer them a reasonable price, a good service and very patiently try to [improve].”

Macro shift

There are undoubtedly aspects of the new trading environment that have showcased Citi’s strengths. Citi has been ranked as the largest in FX trading by revenue for 10 years, according to data provider Coalition Greenwich, and it is now the second-largest bank in rates trading after significantly improving its standing in local market rates in recent years.

Its close ties with corporate clients, which account for about a third of Citi’s markets business, has proved invaluable when companies need help managing large swings in interest rates and commodity prices. Citi has hired more staff in commodities to help win large-scale transactions – a major focus for the bank across asset classes as it looks to capture a greater share of lucrative, blockbuster trades.

“We did far more large-size transactions in 2022, usually associated with M&A or financing or a big commodities or FX transaction. You need to have the banking relationships and you need to be able to wear the risk in the underlying product. There are only three to four banks that can do that,” Morton said.

He was also quick to highlight the stability of Citi’s trading revenues. "There are very few days when we lose money," he said – despite the increasing frequency of sharp market reversals that have accompanied events like the failure of Silicon Valley Bank in March and the UK pension fund crisis last September.

Such events are hard to predict as they are usually linked to some technical feature in the market, Morton said, “some pipe that isn’t big enough". But he characterises these periodic blow-ups as “an important feature of the market that is here to stay, which makes it very difficult for risk managers”.

And what about the outlook for financial markets more generally? “The Fed is done hiking. Inflation seems to be coming down faster than it went up,” said Morton. “Ultimately, that will be really good for risk assets. There’s 500bp of free cushion there that can help.”