Just over a year ago sovereign bond investors seemed to scoff at the notion Russia might launch a full-scale invasion of Ukraine.

The Eurobonds of both countries were generally trading around par. Despite steady tension since Russia annexed Crimea in 2014, most refused to believe Russian president Vladimir Putin would go further and send troops deeper into his southern neighbour.

But by the end of February 2022 such instruments were marked down severely, to a third of their face value, as the market tried to factor in what the invasion on February 24 meant for the debts of each country.

Initially investors looked more favourably on Ukraine. The country’s finance ministry indicated it wanted to keep current on its obligations as far as possible. For Russia, there was more of a stampede as investors rushed to get out before full sanctions were imposed on secondary trading.

But the picture changed over summer. Ukraine accepted it needed to preserve its scarce resources and asked its creditors for relief. A two-year suspension to its debt payments was swiftly granted and a liability management exercise followed.

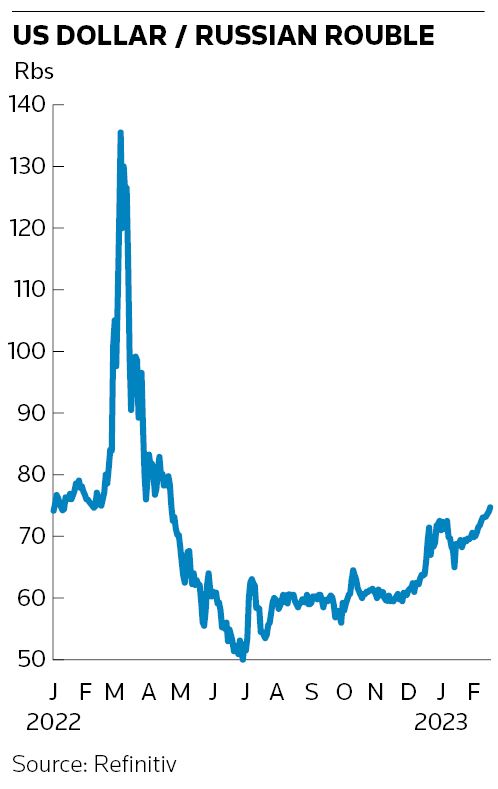

Russia, meanwhile, made use of clauses in its more recently issued bonds allowing it to switch payments into roubles. Increasingly investors seemed happy to accept this as the rouble recovered rapidly after initially halving against the US dollar in the first weeks of the invasion.

By the end of the year, Russia's bonds were bid at around 42 kopeks in the rouble, with little trading taking place. But with the clock ticking on Ukraine’s two-year extension, its bonds have generally drifted down to below 20 cents in the dollar.

Wider impact

The debt restructuring situations both countries faced were idiosyncratic but the solutions showed some useful innovations.

In particular, the clause in some of Russia’s debt allowing it to switch payments into domestic currency could be attractive to other emerging market borrowers, according to a study by Michael Bradley and Irving De Lira Salvatierra of Duke University, Mark Weidemaier of the University of North Carolina and Mitu Gulati of the University of Virginia.

“Despite its sordid provenance, Russia’s sanctions-busting clause might turn out to be a positive innovation that could benefit countries facing unexpected crises. Indeed, had Ukraine included such a clause in its bonds, the benefit would have been enormous,” they wrote in a recent paper.

The example of Ukraine's rapid debt freeze and LM exercise might also prove instructive.

“[Those moves] showed that when you have a legitimate case, where the numbers cannot be challenged or tweaked by those in the official sector, you can build a consensus and get it done,” said one sovereign debt restructuring adviser.

A legal expert in this field said it helped, for Ukraine, that the moral case was clear cut. “It was a necessary thing. What hedge fund manager would want to be in a newspaper opposing a short period of debt relief in the middle of all this?”

He said time remains short for Ukraine’s next move before it has to resume its debt payments. “It runs out in September next year so something will have to be done to address this between now and then.”

Others are already looking at how to sort out the mess once the war finishes, with some estimating Ukraine’s reconstruction costs at up to US$1trn. But huge uncertainties abound about who will pay for this and how. Some have suggested that Russian central bank assets frozen outside the country might be used.

Another important concern is that unpaid claims could put off institutions, including the International Monetary Fund, from providing new finance for Ukraine.

“This is going to be a huge enterprise and everyone is putting pressure on the IMF,” said the legal expert. Ukraine received US$31bn in grants and loans last year and has said its deficit this year will be US$38bn, even before any reconstruction is factored in.

“At the end of this conflict, Ukraine is going to owe its allies a huge war debt for all the arms that were not given in the form of outright gifts. No one is talking about what is going to happen to all that,” said a second legal expert.

In another paper published last week, Lee Buchheit, former partner at law firm Cleary Gottlieb, and Gulati, a professor at UVA's School of Law, said there needs to be more focus on how to resolve situations after the war, when all manner of claimants might seek restitution.

“Many of these are not 'creditors' in the strict sense of parties from whom money has been borrowed. They are rather better described as 'claimants': persons or entities with claims against the financial resources of the state,” they wrote. “A process that deals with a country’s conventional obligations for borrowed money but which does not resolve sizable claims of other kinds is obviously fragmentary and insufficient.”

Bold move

The bold moves taken by Ukraine seem to have spurred those involved in other debt restructurings to try and accelerate their own negotiations. Afflicted countries want to avoid the situation in Zambia, which defaulted in 2020 but is still waiting to start serious negotiations with creditors.

The stumbling block here is that China is Zambia's biggest creditor and, despite signing up to the G20’s common framework, remains reluctant to play according to those Paris Club rules, which seeks consensus among all official sector creditors before private sector creditors take the same hit.

China has indicated it would prefer simply to extend its loans for a long time with no haircut. It has yet to provide the IMF with assurances that it will offer the fund’s designated debt relief to Zambia and other distressed countries like Sri Lanka.

“There is a growing sense of frustration at not being able to get the common framework off the ground,” said the first legal expert. “Nothing has moved in Zambia for two years. It is a torturous process. China has perceived this forum as Western powers coming to beat it up.”

The restructuring adviser said diverging interests in sovereign restructuring was nothing new, noting that the Paris Club had previously accepted the option of debt servicing reduction – rather than simple debt reduction – for Japan in the past. This is what China is effectively asking for, he said.

“This menu of options is what you can see being revived under pressure from China, which is asking for no principal reduction but a reduction in debt service costs over a very long period of time,” he said. “This is history repeating itself. There would be comparability of treatment and I see no reason why it could not work with China being in the process. China is asking the right question but has some difficulty in catching up and accepting the rules of the game.”