On February 24 2022, Russia invaded Ukraine, in the process raising issues about the global geopolitical and economic landscape in ways that were unimaginable before.

The invasion, and the subsequent sanctions imposed against the Russian state and certain companies and individuals, also brought to the fore issues for the international financial markets to address – on the outlook for the emerging markets asset class, on geopolitical risk, on the payments process, and on the question of what exactly is a default. In the months following Russia's invasion, it seemed that the very nature of the international financial system would be irrevocably altered by an unprecedented crisis. This wasn't a balance-of-payments sovereign debt crunch or political event of the kind that EM investors typically grapple with.

"It was quite different from the usual crisis. There was a sense of disgust, not just from investors but the whole world," said Sally Greig, head of EM debt at asset manager Baillie Gifford, which was heavily underweight local currency Russian debt at the time. "Even if you were personally thinking of picking up Russia at a few cents, your clients wanted you to have nothing to do with it. You don’t usually get that. In a normal crisis, distressed investors fish around. There were a few, but far fewer than usual."

Russia remains a pariah state. And Ukraine's experience continues to be a tragic one. Yet, a year on, what's striking is, specifically in terms of the capital markets, how little else has changed in practice. For most EM investors the war cast only a relatively brief, albeit intense, shadow over their daily business, as those that held positions in Russian entities scrambled either to get out of them or work out if they could still receive payments on their holdings – until the US authorities closed down any potential route to do so in late May.

Back where it was

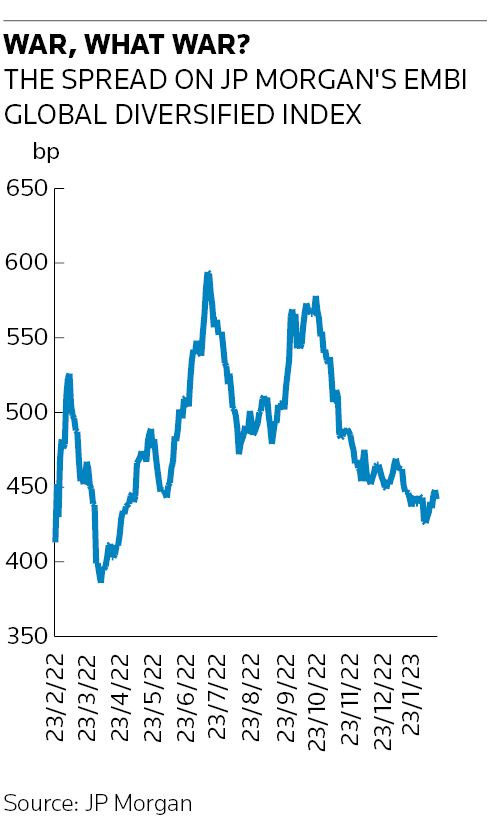

Over the past year moves in rates markets have had a much bigger impact on EM portfolios than the consequences of the war itself, with global central bank decisions dictating moves in the asset class. Indeed, EM debt suffered record fund outflows of more than US$87bn in 2022, which equates to over 10% of the asset class, according to Lazard Asset Management, citing data from EPFR and JP Morgan. However, as a rally took hold in the fourth quarter, fund flows began to turn positive again, a theme that has continued into this year.

"Credit spreads in most of the EM universe are broadly back to where they were before the invasion – apart from idiosyncratic distressed credits," said Richard Briggs, senior fund manager at Candriam, which had excluded Russian sovereign debt from its investable universe across its sustainable strategies many years before the invasion. "Returns have been weak but mostly because of Treasuries – the war has not had a lingering impact on the rest of the EM index. Even on the commodities side, the oil price is lower than it was before." The price of a barrel of Brent crude oil was US$95 on the eve of the war; it is now quoted at US$84, according to Refinitiv.

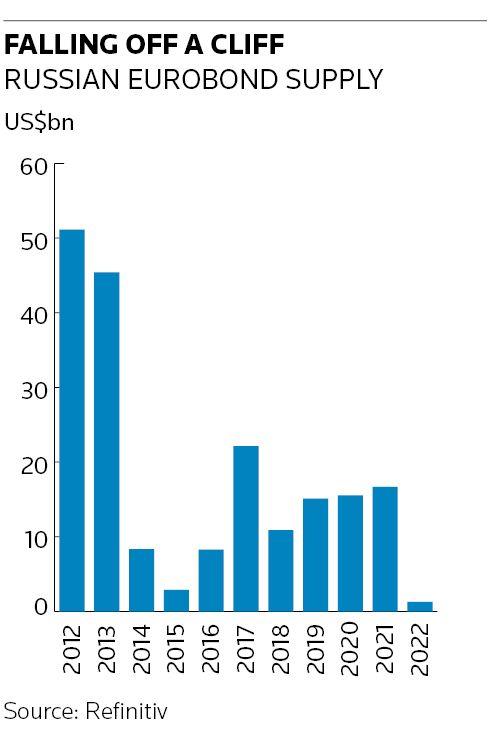

There were two obvious ramifications for EM investors as sanctions began to be rolled out by the US and Europe: one, that Russian Eurobond issuance was frozen, so a chunk of supply would be lost for the foreseeable future; and two, once JP Morgan eventually decided to throw Russia out of its series of emerging markets bond indices, institutional investors would have to trade out of their positions.

Neither, though, have had any long-lasting repercussions.

Russian-related supply had been slipping ever since Moscow annexed Crimea in 2014, following which the first set of sanctions were applied against certain Russian entities and individuals. After reaching US$51.1bn of supply in 2012 and US$45.4bn in 2013, overall Russian issuance volumes had fallen to between US$8bn and US$17bn from 2014–2021, with the exception of 2017 when just over US$22bn was sold, according to Refinitiv data. To put that into context, there had already been more than US$25bn of supply from Central and Eastern Europe for this year up to February 10, according to Refinitiv, and US$52bn from emerging Europe, Middle East and Africa.

Russia's exit from the indices at the end of March 2022 was more meaningful in the short term. As a key member of JP Morgan's emerging market bond indices, Russia's weighting on February 23 in the local currency GBI-EM Global Diversified Index was 6.12%, while in the hard currency EMBI Global Diversified Index it was 2.7%. Russian corporates were also represented in the bank's relevant indices.

"It was more pronounced on the local currency side," said Viktor Szabo, investment director for EM debt at abrdn. "My feeling is that people were overweight as Russia was quite a good story – very strong macroeconomics and conservative policymaking. As a bondholder you want that combination of a strong balance sheet and high level of reserves."

By throwing Russia out of the indices, JP Morgan's move enabled investors benchmarked against them to benefit. "It was a full writedown, so ironically gave a technical outperformance," said Claudia Calich, head of EM debt at M&G Investments, which had exposure to both Russian hard and local currency bonds. "If you had Russian securities on your books during their removal from the indices, they were valued at a mid-market price higher than zero."

As investors dumped their Russian holdings, there was a general reweighting to other markets and regions. "Latin America was a big beneficiary," said Greig. "It was geographically distant, which helped as we didn’t know what was going to unfold, and the countries are mostly commodity exporters benefiting from price increases."

In the immediate aftermath, any neighbouring country to the region, even though not directly involved in the conflict, became a no-go area for many investors, as did any potential issuer with any exposure to Russia. Twelve months on, though, and those concerns have mostly faded. Hungary, for instance, a country which voted in favour of EU sanctions but gained exemptions over Russian oil and gas supplies, has successfully issued a number of times across different currency markets since June.

Those issuers with direct Russia exposure, though, are having to issue at relatively more expensive levels. Raiffeisen Bank International's funding costs, for example, are higher since the outbreak of the war – though its more attractive spreads meant its most recent deal, €1bn four-year non-call three senior preferred in January, drew €2.8bn of orders.

Headless chickens

Modelling risk/reward considerations is what investors are paid to do. But some believe investors are underestimating the risks.

"Capital markets participants sometimes behave like headless chickens," said Gustavo Medeiros, head of research at investment manager Ashmore, referring to how many are ignoring the real lessons of the war. "What did change is that we have to be more aware of geopolitical risks."

The sheer scale of the sanctions against Russia was something that EM investors had never encountered before. "We had seen sanctions against Afghanistan, for example, but not against such a big middle-income country. This was new and quite shocking for investors," said Greig.

Anticipating geopolitical risk, however, is much harder compared with anticipating domestic political risk. "Geopolitical risk is, by definition, much more fluid," said Calich. "There are global repercussions, whereas a political event is much more contained to a specific country."

Investors do have recourse to hedging strategies but modelling specific geopolitical risk is next to impossible. The consensus trade in the run-up to the war, for example, was to be long Ukraine based on its underlying credit story. And if there was no war, investors would likely have made good returns. As it turned out, an appropriate strategy was probably to have been long Ukraine, short Russia – and then closing those positions before the market froze.

Perhaps one way to manage these risks better now is to apply stricter investment criteria. "We didn’t have any Russian exposure. There was a good argument for holding Russia in terms of debt coverage ratios and low levels of debt. But it was not somewhere we could justify investing. We were not being paid enough for the risks involved," said Carl Shepherd, an EM debt-focused portfolio manager at Newton Investment Management.

Moreover, greater awareness of ESG means investors will be under growing pressure to justify their exposure to certain states, although managing potential geopolitical flashpoints depends on instinct. "It's tricky ground," said Szabo. "A lot of ESG is being driven by regulation. The starting point was the environmental pillar, now it's moving to social, but there's a long way until we get to geopolitics. It’s not an objective set of values."

Weaponisation

It's not just dedicated EM fund managers, however, who need to think more deeply about geopolitical risks – the entire investor community has to. Most, though, go about managing the risks the wrong way, according to Medeiros. "Most asset allocators think about geopolitical risk from a reputational risk perspective rather than P&L. No one is thinking about their value-at-risk of an event," he said.

By this he means the repercussions of any big geopolitical crisis could be far-reaching, beyond the leading actors of a conflict, exposing risks but also presenting relative value opportunities in ways that investors aren't properly thinking about. "There's a big landmass of neutral countries that should be beneficiaries of capital flows during geopolitical crises," he said. "Most EM countries remain neutral during geopolitical crises and neutral countries are geopolitical safe havens. Investors need to price in geopolitical risk properly. Is that happening? I'm not sure."

The other issue exercising Medeiros is the role of the US dollar in the global financial system – or as he describes it "the weaponisation of the dollar".

One of the unforeseen consequences of the invasion was how sanctions blocked Russian borrowers from making US dollar payments even though they were willing to do so, but couldn't as investment banks and clearing agencies stopped processing coupon and principal payments of foreign-currency Eurobonds. Moreover, the freezing of offshore Russian US dollar assets, principally those of the central bank, was unprecedented in terms of scale and coordination.

"The weaponisation of the dollar payments system wasn't new. It had happened with Iraq, Iran and Afghanistan. What was new was the weaponisation of the dollar in a globally important systemic country, particularly in terms of commodities and capital flows," said Medeiros. "Russia had about US$1.65trn of dollar assets and US$1.15trn of liabilities at the end of 2021. A large portion of these liabilities couldn’t be repaid, and a large portion of assets were frozen. That is meaningful."

For some, what happened was unique. "Russia was a very particular set of circumstances," said Greig. "Yes, it does raise the question of what happens if a country is not allowed to make its payments but my assumption is the vast majority of times the system works. I'm more concerned about capital getting locked up in countries and delays in money coming back to investors. We've had to wait for a month for money to come back from Egypt, for example."

But for others, the shocks stemming from Russia's invasion could yet be surpassed. "The big question now is China," she said. "How far would Western countries be willing to go in applying sanctions? That would be much harder for investors. It's important to think about these things sooner rather than later."

Additional reporting by Robert Hogg