There’s nothing like the most turbulent fixed income market in decades to provide a thorough stress test of the infrastructure underpinning modern finance. So it should please regulators that LCH’s SwapClear, the middleman in nearly US$400trn of interest rate derivatives trades, has succeeded in keeping a low profile amid this year’s market fireworks, while also clearing record volumes of transactions.

“Our preparations for these types of situations have been paying off,” said Susi de Verdelon, head of SwapClear and listed rates at LCH. “It’s very active: markets are very busy and firms are positioning and hedging more."

It’s hard to overstate the speed and scale of the move in interest rates this year. Supply-chain bottlenecks and Russia’s war in Ukraine sent inflation spiralling to levels last seen in the early 1980s. That has forced the US Federal Reserve to raise interest rates to nearly 4% from just above 0% at the start of the year. Other central banks have followed similar paths.

And that has led to a surge of hedging activity passing through SwapClear. "Two years ago, central banks had near-zero interest rate policies and there wasn’t much short-dated swaps activity. Now, there’s a lot of uncertainty over the path of central bank rates,” de Verdelon said.

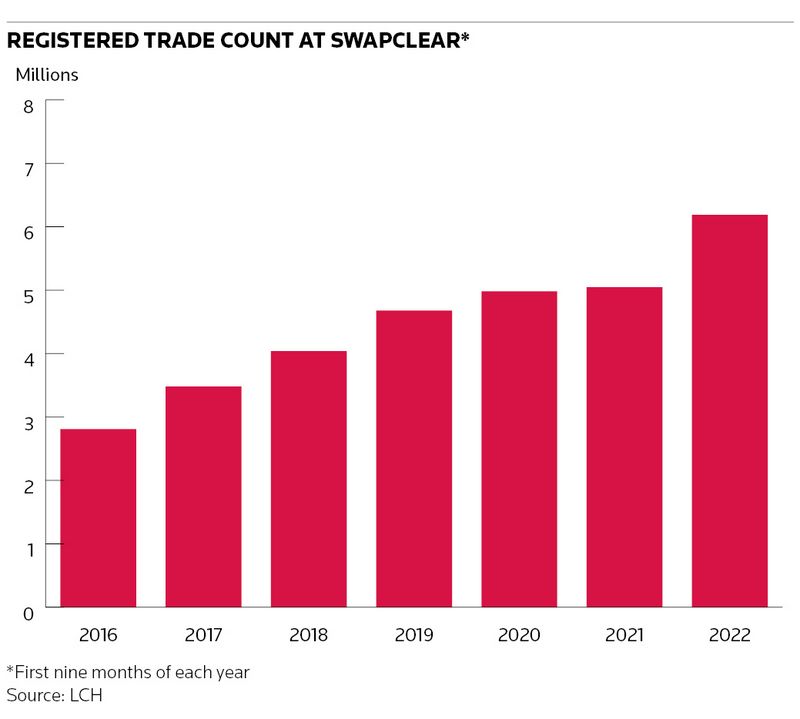

LCH (which is owned by London Stock Exchange Group, IFR's parent company) says interest rate swaps cleared at SwapClear account for more than 90% of all cleared interest rate derivatives activity, leaving it well placed to benefit from an upswing in activity as investors reshuffle positions. Registered trade count at SwapClear increased 23% in the first nine months of the year to a record 6.2m.

“It’s been a real paradigm shift from a low, static interest rate environment into something very different with a major rebasing of inflation and interest rate expectations,” said David Horner, chief risk officer at LCH. “There’s an increase in volatility because there’s a lot of uncertainty. Previously, there was no change from central banks for years. Suddenly, rates are moving 100bp in a very short space of time.”

Margin call

Derivatives clearing was one of the central global reforms following the 2008 financial crisis and so attracts significant scrutiny – both regulatory and political – for what was once considered a humdrum piece of financial plumbing. Politicians have locked horns over its location, while regulators have fretted whether their efforts to prevent future systemic meltdowns has ironically created the mother of all “too-big-to-fail” institutions.

Market volatility can pose serious challenges to central counterparties and exchanges, prompting a thorough examination of their risk management and margin processes. Margin calls across the finance industry have rocketed this year as markets whipsaw – quite literally off the charts in the case of the UK following the government’s disastrous “mini-budget” in September – exposing vulnerabilities in the financial system. Some firms have already come under fire for their handling of events. The London Metal Exchange, for example, is facing investor lawsuits after cancelling nickel trades in March following a surge in futures prices.

CCPs like SwapClear sit in the middle of derivatives transactions to minimise the risk of defaults among swaps traders cascading through the wider financial system. One way they do this is requiring derivatives users to post collateral to reflect changes in the valuation of their positions. This “variation” margin complements another line of defence: the “initial” margin firms must stump up, which serves as an extra cushion in case one of the counterparties defaults.

A sustained pick-up in volatility usually prompts CCPs to increase the size of that cushion to ensure they have enough protection as markets become choppier. But CCPs must tread carefully. Asking for too much collateral too quickly may exacerbate stresses in the system, particularly if it causes cash-strapped clients to sell assets en masse to meet margin calls.

LCH data show that total initial margin at SwapClear rose to £159bn at the end of June, a 12% increase from a year earlier. That compares with a small decline in margin at CME Group for interest rate swaps, according to data and analytics firm ClarusFT, but is far below the 177% jump to €44bn Eurex registered.

“We are very cognisant of procyclicality risk when we design our margin models,” de Verdelon said. “The models are designed to respond to stressed market conditions, but gradually and in a proportionate way.”

The extreme moves in UK rates markets after the mini-budget have already caused a sharp jump in initial margin levels for sterling swaps, according to ClarusFT. John Wilson, a consultant and former banker specialising in clearing, said the moves in UK rates (as well as other markets) will be baked into margin models for some time, increasing the demand on firms to have more collateral in the system.

“This year's market volatility means the cost of clearing has gone up," Wilson said.

Horner said LCH's margin models have various drivers, including historical data. "But even in a very volatile period of time, the models are designed with internal buffers to fade those moves and to return margin as soon as conditions warrant,” he said.

Market boom

SwapClear traces its origins to the late 1990s when it started catering to the burgeoning market for interest rate derivatives. Banks trading these products were wary of the heightened counterparty credit risk involved in swaps contracts that could last 30 years or more and liked the idea of a central body where they could net down their exposures. That led many to clear their interbank activity voluntarily well before regulators mandated any such move.

The collapse of Lehman Brothers in 2008 soon illustrated how CCPs could help reduce risks threatening the wider financial system. LCH resolved Lehman’s US$9trn cleared interest rate swap portfolio spread across more than 66,000 trades in the space of three weeks, without forcing losses onto other clearing members.

Regulators subsequently mandated clearing for a wider range of derivatives users and instruments, pushing nearly 80% of the interest-rate derivatives market into CCPs. CME Group, Eurex and others developed interest rate clearing offerings, but the incumbent LCH took the lion’s share as clients looked to concentrate most of their activity in one place to lower costs.

Clearing even became something of a political football. Since Brexit, the European Union has pushed for a larger portion of euro swaps clearing to migrate to its shores. De Verdelon declined to comment on euro clearing, beyond noting LCH has a "very strong dialogue" with EU regulators and customers, and that LCH is directly subject to EU law and ESMA supervision.

More recently, some have questioned the role clearing may have played in exacerbating the liquidity squeeze among UK pension funds during this year’s Gilt market meltdown. Pension funds aren’t currently mandated to clear, though the EU is set to end a temporary exemption for the sector next June.

Horner said that the majority of pension funds don’t clear their swaps today, opting to manage them bilaterally instead. Overall, he said that clearing “is an effective risk management tool".

Libor reform

Elsewhere, LCH has been focused on the historic transition away from the troubled Libor lending benchmarks to new reference rates. It has already moved Swiss franc, euro, sterling and yen contracts to alternative reference rates, shifting about 350,000 contracts over the course of two weekends.

The US dollar Libor transition is even larger still “but it’s going well", de Verdelon said. LCH began the year with about a million trades referencing US dollar Libor and now has close to 700,000. Any trades that remain will be converted in April and early May before the mid-2023 cut-off date for the end of Libor.

“It’s a very significant event for all members and we’re making very intensive preparations,” said de Verdelon.