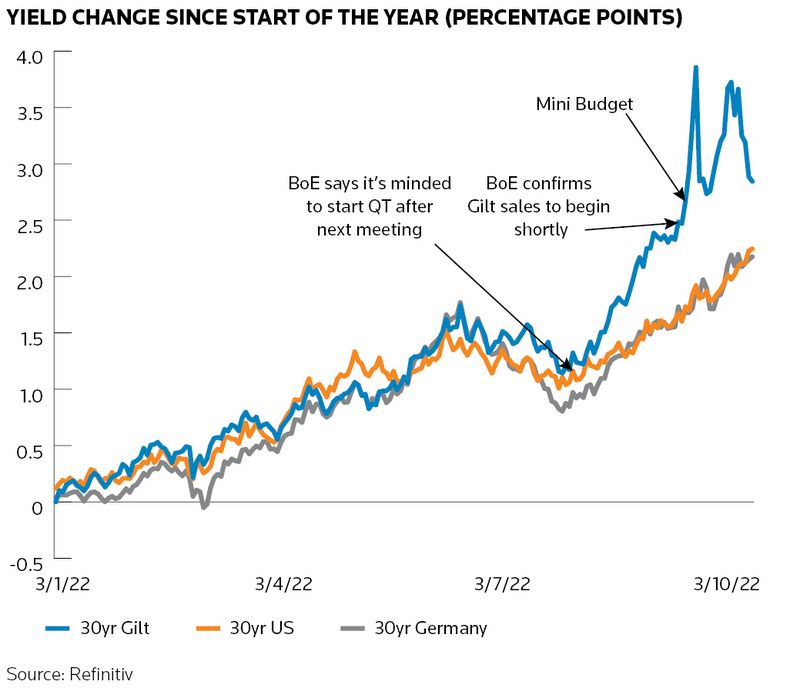

Gilt markets have come under intense pressure this year. Yields started to climb as it became increasingly apparent that inflation was becoming entrenched, prompting the Bank of England to raise interest rates and set out a plan to sell its Gilt holdings.

The selloff accelerated after the UK government pledged large, unfunded tax cuts in September, forcing the BoE to intervene temporarily to calm Gilt markets. Those fiscal plans have since been mostly reversed, leading to the resignation of Prime Minister Liz Truss on Thursday.

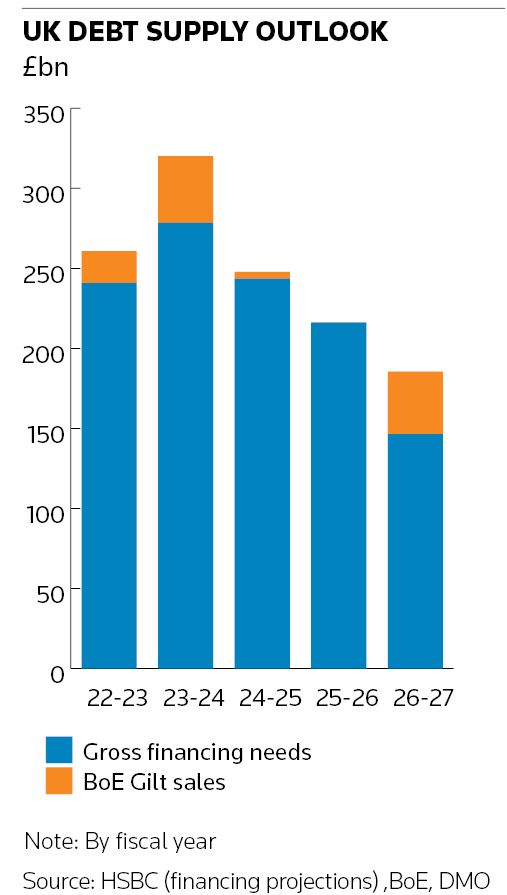

Despite a recent stabilisation in yields, investors have voiced concern about the start of the BoE’s “active quantitative tightening” next month, when it will start to sell Gilts. The BoE’s gradual exit will deprive Gilt markets of one of their largest buyers of recent years at a time when the government’s financing needs are set to increase markedly.

Here are six charts that illustrate the pain in Gilt markets this year – and the challenges that lie ahead.

The selloff in long-dated Gilts started outpacing moves in US Treasuries and German bonds in August. That coincided with the Bank of England saying it was “provisionally minded” to start Gilt sales shortly after its meeting the following month. Confirmation that the BoE would soon proceed came in September, just before the government’s infamous “mini-budget”, which poured further fuel on the Gilt market fire.

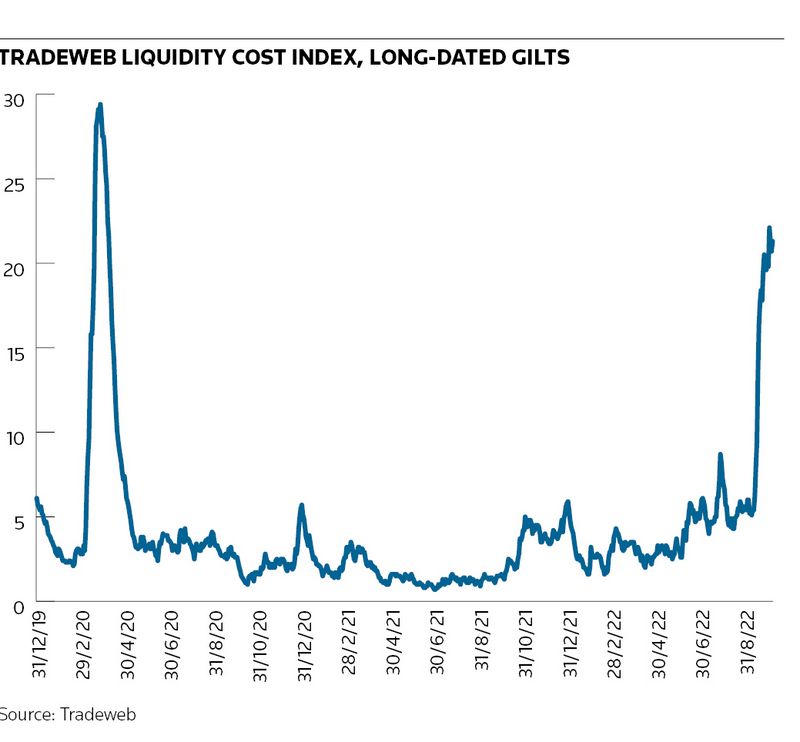

Trading conditions in Gilt markets deteriorated sharply after the mini budget. Nicola Danese, Tradeweb’s head of European fixed income, noted that this was a UK-centric issue and that liquidity metrics in Gilts “definitely improved” after the BoE intervened. “The price of liquidity in Gilts has changed, but this hasn’t really translated into a reduction in volumes – quite the opposite in fact,” Danese said.

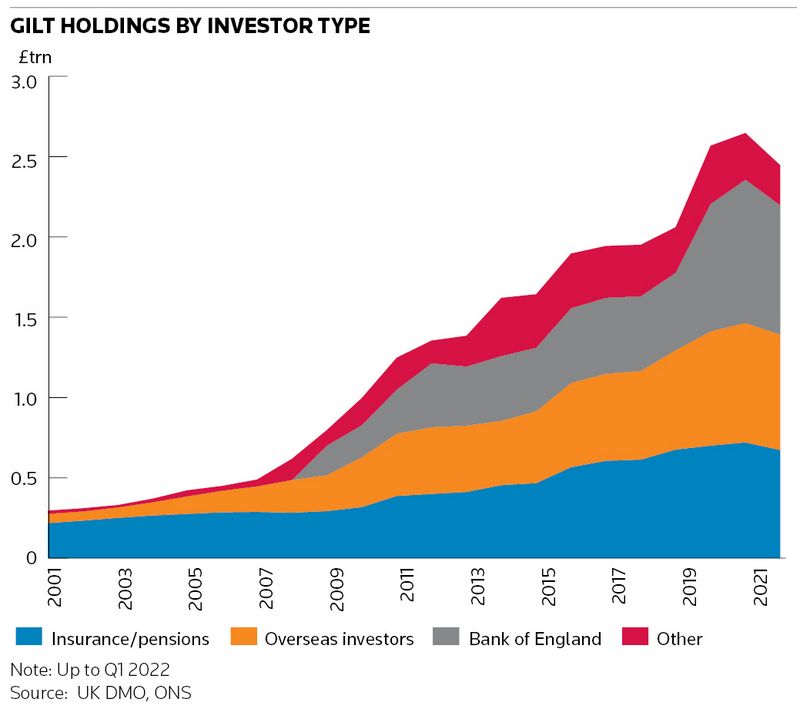

Turmoil among UK pension funds using LDI strategies had created a self-reinforcing cycle of fire sales in Gilts before the BoE announced its emergency purchases in late September. Pension funds have been a core investor in Gilts over the years, while the BoE has been another stalwart.

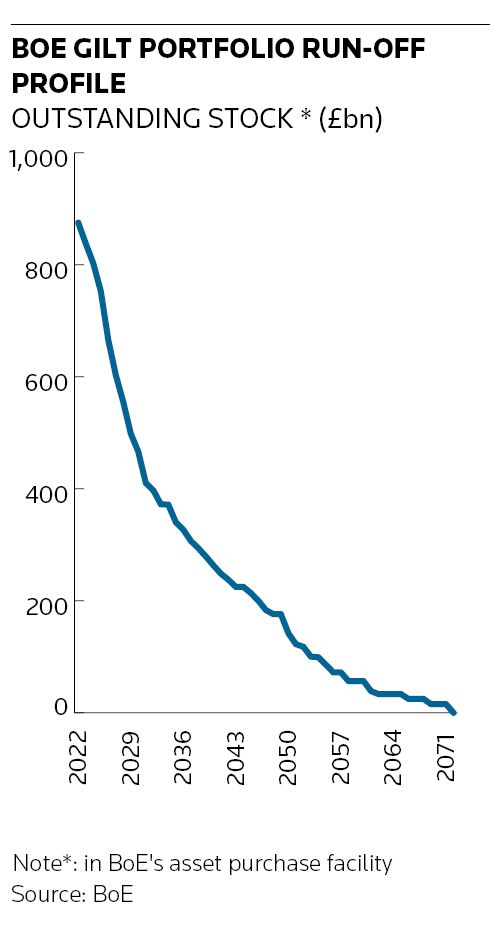

The BoE halted its emergency purchases on October 14 and has now confirmed it plans to go ahead with Gilt sales from November 1. Analysts say the long-dated nature of the BoE’s Gilt portfolio may have encouraged it to opt to sell some of its holdings rather than relying solely on them rolling off naturally, as the US Federal Reserve has decided. The BoE’s portfolio doesn’t run off until 2071 and would still be over £400bn in size at the end of 2030 without active sales.

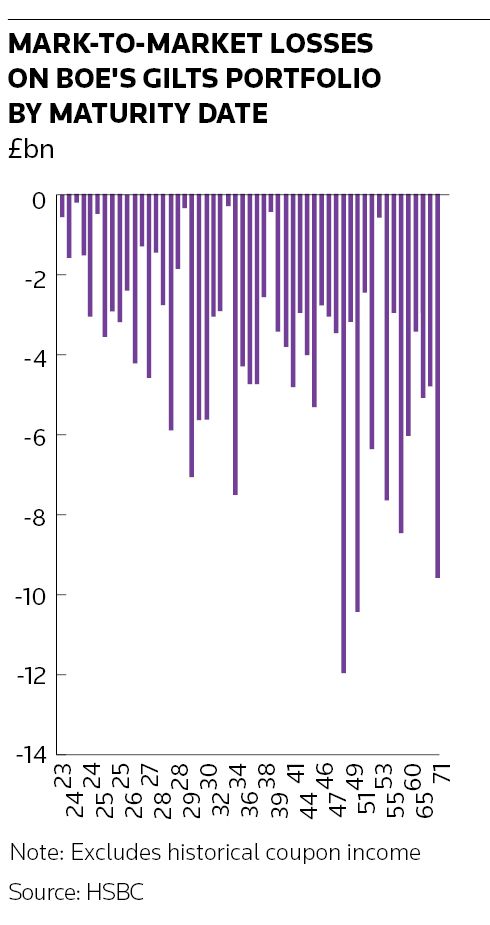

The BoE has said it will initially avoid selling longer-dated Gilts, which were at the centre of the pensions-related crisis. As well as lowering the chances of further market fireworks, that could help reduce losses the BoE will incur from its sales, analysis from HSBC shows. That is because mark-to-market losses are smaller on the shorter-dated bonds the BoE holds.

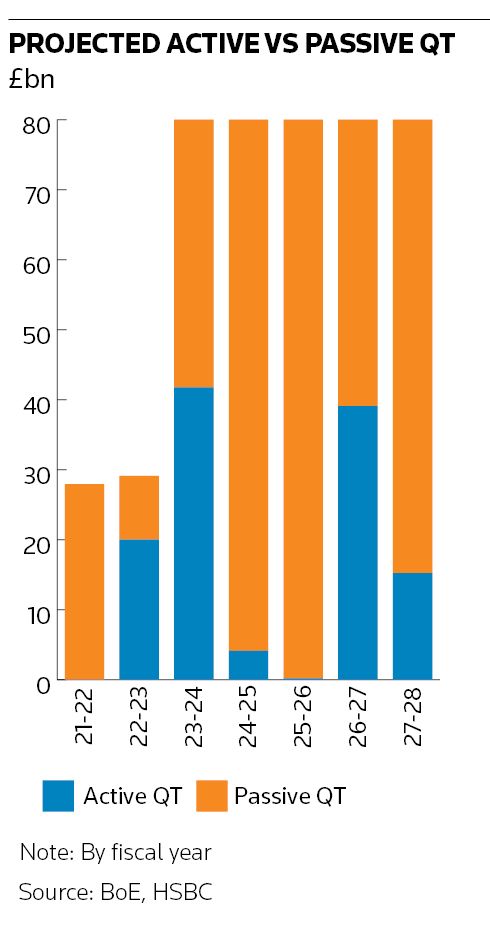

The good news for Gilt markets is that much of the BoE’s proposed £80bn annual shrinking of its Gilt portfolio can be achieved “passively” through bonds maturing naturally in the next few years, reducing its need to sell. That’s just as well considering the UK’s gross financing needs are projected to balloon to about £278bn in the next fiscal year, according to HSBC. Layer on top of that about £42bn of Gilt sales from the BoE under QT and there looks set to be a record amount of UK debt for investors to absorb.