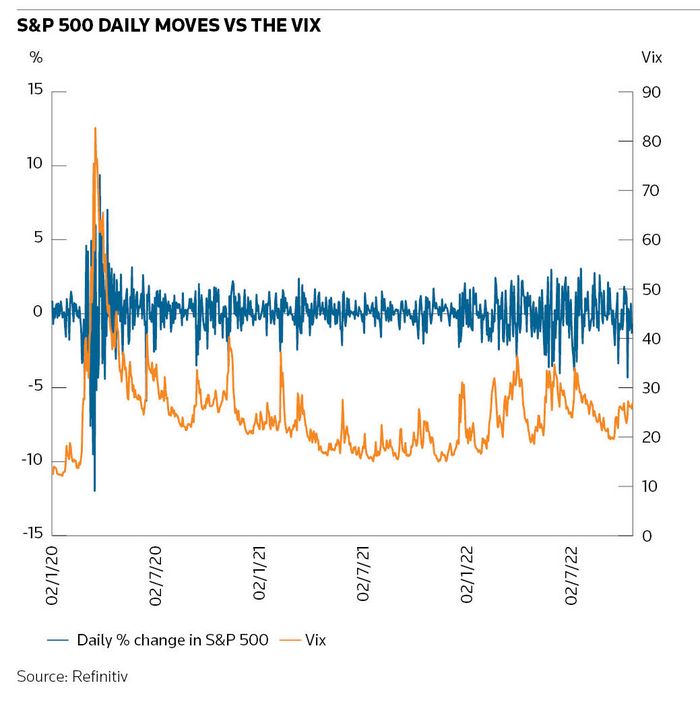

The S&P 500 recorded its worst session of a terrible year when it slid over 4% on September 13. One closely watched barometer of stock market health told a different story that day, though, as Cboe’s Volatility Index – the VIX – only inched up a few points.

The mild reaction from a benchmark often referred to as Wall Street’s fear gauge confirmed a trend that has confounded investors this year: equity volatility remains subdued even as stocks record their worst performance since the 2008 financial crisis.

Traders identify a number of factors contributing to this seeming paradox, with a surge in hedging activity among fund managers being chief among them. That has provided investors with a measure of protection against market declines, traders say, while potentially leaving them vulnerable to a steep lurch lower in prices.

“There is less reason for volatility to pop when the market is grinding lower with relatively small daily price changes, especially given that investors have been consistently hedging," said Pete Clarke, global head of derivatives strategy at UBS. "That’s in large part why the equity volatility response has been muted so far this year."

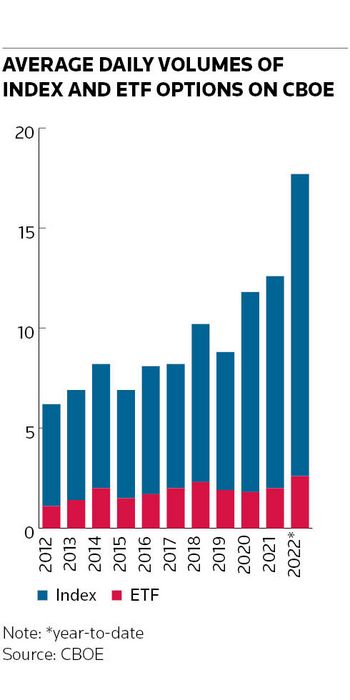

Options trading data show the scale of hedging activity across the market. Cboe says its average daily options volumes are running at record levels in 2022, driven by an increase in options on exchange-traded funds and indices as investors have looked to insulate their equity portfolios. Demand for put options, which offer protection against share price declines, has also increased markedly from last year, data from the exchange show.

Bankers say investors have favoured so-called premium-reducing hedges in particular, such as put spreads or knock-out options. These types of strategies are cheaper than a traditional option, but will only provide protection against a decline in equity markets up to a certain point. That reduces the need for investors to panic sell or hedge as long as equities only plod lower, rather than nosedive.

Clarke said these lower-premium hedging strategies had also helped bank trading desks to manage the associated risks, reducing their need to hedge too.

“These compromise hedges leave dealers long downside volatility, and mean that they are in a better position to manage their own risks,” Clarke said. “That can help keep a lid on implied volatility as long as we don’t get the second shoe dropping. Investors are well positioned for grinding moves lower, but much less so for violent rallies or declines.”

The worry factor

The VIX produces a broad measure of equity volatility by aggregating prices of short-dated S&P 500 options, which traders use to bet on rises or falls in stock markets. Those options prices tend to increase when share prices wobble, pushing up the VIX in turn, to reflect the greater level of uncertainty over the market outlook.

Equity volatility laid dormant for much of the previous decade as central banks pinned interest rates near to zero and bought vast quantities of bonds to stimulate their lacklustre economies. That changed in 2020 when the coronavirus pandemic shook equity markets from their slumber and sent the VIX rocketing to 83 points – its highest level since 2008. It went on to close above the 40 mark on 34 occasions in the first half of 2020 as investors struggled to discern where prices were headed next.

This year has been a different story. The VIX peaked at 36 shortly after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and has since averaged only a handful of points above levels registered in 2021, when equity markets were in a bull run. That calm demeanour seems at odds with the deepest slump in global equity prices since the financial crisis. It also contrasts with a more pronounced increase in volatility in markets linked to interest rates, currencies and commodities, which have been convulsed by the war in Ukraine and central banks withdrawing monetary stimulus to fight inflation.

“Being long equity volatility worked spectacularly well in 2020 and this year it hasn’t – it’s underperformed versus pretty shaky markets," said Alastair Beattie, head of alternative risk transfer at Societe Generale. "That’s been one of the questions we’re most commonly asked, both in terms of intellectual curiosity and because of frustration from some clients that had long vol exposure to hedge their portfolio – it hasn’t done what they might have hoped.”

Portfolio protection

One dynamic that seems to have helped lower volatility is that investors entered 2022 in a more circumspect mood as equities hovered at record highs. That wasn't the case in 2020, when the sudden outbreak of the global pandemic blindsided many including bank trading desks, which had to scramble to hedge structured products books.

“We entered the Russia crisis at a relatively elevated level of implied volatility, skew and convexity. That means you really need to have a sharp downside move to trigger an overreaction and hedging. People were protected so there was no panic – there was less scope to have the kind of spiralling effect we saw in 2020,” said Herve Guyon, head of flow strategy and solutions for Europe at SG.

One sign of the lack of panic in the market is the flatness of skew – the difference in price between options of different strikes. Among other things, that suggests investors haven't been scrambling to buy protection against a full-blown market crash.

"We have constant discussions with clients on tail hedging, but I’d argue we spend more time discussing ways to cheapen puts for clients rather than buying large outright options hedges," said Quentin Andre, global head of equity derivatives sales and structuring at Citigroup.

Bankers note other factors that are contributing to the calm environment. In the past, dealers have had more sensitivity to skew as a result of "Cliquet" activity, where US insurers sell upside calls that reset on a regular basis. That sensitivity has declined this year as falling markets have reduced the need for dealers to hedge upside moves, according to Guillaume Flamarion, co-head of the multi-asset group at Citigroup.

Elsewhere, the trend of banks selling more hedges through equity puts, that knock out if volatility hits a certain level, has forced dealers to sell more volatility when the market drops, Flamarion said, pushing implied volatility down further.

Still, even though volatility is low at present, few are willing to write off a bigger spike if weakness in equity markets intensifies.

“If you have a more serious sell-off, some autocallable structured products could go through 'peak vega' and volatility could spike. The way it was up until now has been relatively mild, but the dynamic could reverse quickly,” said Flamarion.