Britain’s top banks are awaiting guidance from new Prime Minister Liz Truss that could affect more than £2bn of annual taxes. Tax experts reckon the net result will be little change in the rate they pay, but will add complexity this year to a system that needs to be simplified.

Banks in the UK have been paying extra taxes for more than a decade to reflect the taxpayer support they received during the 2008–09 financial crisis. The sector reckons it is now time to remove the surcharge – but that appears unlikely given the current strain on public finances and energy price crisis.

Banks have paid about £34bn in extra taxes in the UK since 2010, according to IFR calculations. They paid £3.7bn extra in the 2020/21 financial year, down from £4.7bn the year before, which marked a peak after years of steady increases.

Now, Truss and new UK chancellor Kwasi Kwarteng are assessing how much banks should pay, and there are several moving parts. UK corporation tax is currently 19% and since 2015 there has been an 8 percentage point surcharge on bank profits, giving an effective tax rate of 27%. But following plans to hike corporation tax to 25%, the government said it would cut the bank surcharge to 3% – effectively creating a 28% tax rate. It said that would be a competitive rate compared with rival countries, such as the US, Germany and France. Both changes were due to occur from April 2023.

Truss, however, has said she will not go ahead with the corporation tax rise. That could cut the effective bank rate to 22%, unless she also reverses the change in bank surcharge. She has not yet released details. The opposition Labour Party has said that would amount to a stealth tax cut for banks when the country can’t afford it.

Tax experts and industry sources say it’s likely the surcharge will adjust in an equal and opposite way to what happens with corporation tax. But there could be surprises and clarity may not emerge for some time.

“We’re likely to see a reduction in corporation tax, but if that happens, I can see the surcharge tax going back up again, so the overall level stays at around 27% or 28%,” said Dominic Stuttaford, global head of tax at law firm Norton Rose Fulbright.

“That would make sense. Are you going to end up with a lower rate for banks in the current environment? I would doubt it.”

Stuttaford said it is likely to lead to a busy end of year for banks’ tax departments and they need more details. “A difficult issue is when the details come out and when the changes are enacted. The banks need to see the flesh on the bones,” he said.

Kwarteng met with bank chiefs on Wednesday to discuss issues, including kick-starting the economy and “reducing burdensome regulation and taxes”, according to a Treasury statement. Attendees included CEOs from HSBC, Barclays, Lloyds and NatWest, and senior executives from Goldman Sachs, JP Morgan and UBS.

Time for surcharge to go?

Banks would like to see the surcharge axed. They question why one of the country’s most successful industries has a higher tax rate than other sectors.

Bank lobby group UK Finance estimated the total tax contribution of banks to the UK, including VAT and indirect taxes, was £37.1bn in the year to the end of March 2021. It estimated the total tax rate for a typical corporate and investment bank in London was 44.9% of profits, which it said was similar to Frankfurt and Amsterdam but compared with a rate of 30.2% in Dublin and 29.4% for banks in New York.

“We believe the tax system should treat all sectors equally," said Sarah Boon, managing director of corporate affairs at UK Finance. "At present, the bank corporation tax surcharge and the bank levy mean that, whatever the headline rate of corporation tax is, the banking sector is subject to a higher rate of tax than other sectors. The banking sector-specific taxes make the UK uncompetitive when compared to other global financial centres.”

Norton Rose's Stuttaford said: “Banks would say, perfectly fairly, that the financial crisis was more than a decade ago and should they still be subject to an extra tax? But when Treasury revenues are going to be short, I don’t think that banks are going to be able to win that argument.

“I think it will be hard to reduce the effective rate of tax in the next couple of years. It’s about political and finance issues, and the government is not in a position to [cut the surcharge],” he told IFR.

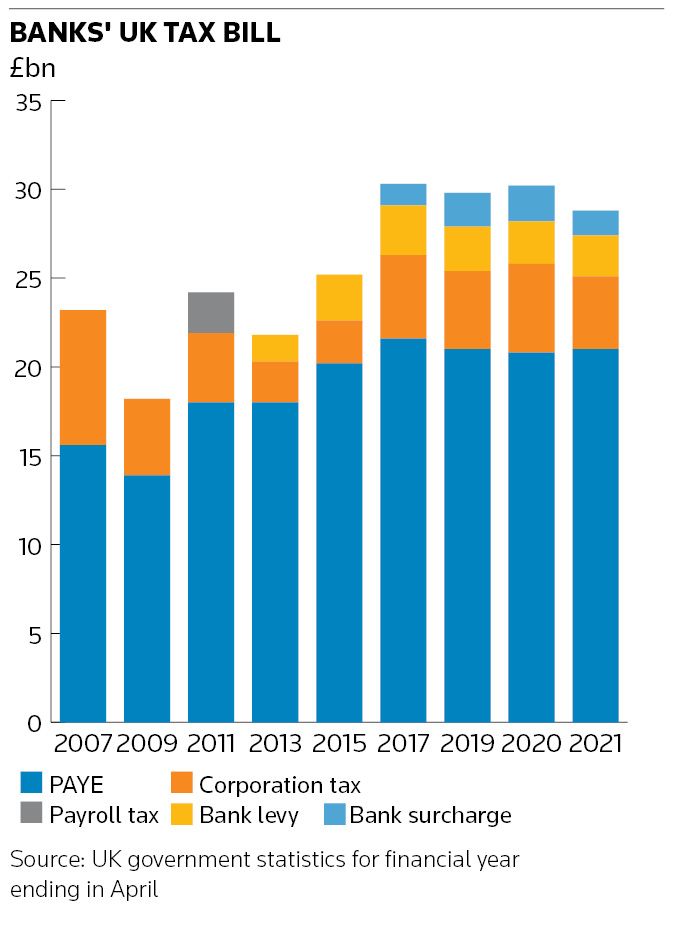

Banks paid £28.8bn in UK taxes in 2020/21, down from £30.2bn the previous year and a high of £30.6bn in 2018/19, according to government data. In the three years before 2008, the annual tax charge was about £21bn–£23bn.

The bulk comes from PAYE payments – income tax on staff earnings and national insurance - which was £21bn of the tally in 2020/21. Corporation tax contributed £4.1bn last year, down from £5bn in 2019/20 as Covid hurt earnings.

But Britain has also imposed several extra levies on banks in the past decade. A payroll tax only lasted one year and applied to bonuses paid in 2010, but raised a hefty £2.3bn. It was replaced by a levy on balance sheets, which raised £2.3bn in 2020/21, and is now being reduced. The 8% bank surcharge has been in place since 2016, and raised £1.4bn for Treasury coffers in 2020/21, down from £2bn the year before.

Taxing year-end

As with all tax issues, what banks pay can vary wildly due not only to tax rates, but complex rules including treatment of past losses and deferred assets, as well as geographic mix.

As NatWest, which is 48% owned by the UK government, said in its latest annual report: “Accounting for taxes is judgmental and carries a degree of uncertainty because tax law is subject to interpretation, which might be questioned by the relevant tax authority.”

Last year, the effective tax rates at the major UK banks varied from 14.1% at Barclays and 14.7% at Lloyds, to 22.3%% at HSBC and 24.4% at NatWest.

Indirect taxes, such as VAT, add even more complexity. When most companies buy goods or services they can generally reclaim VAT, but that doesn’t always apply to banks. Even the UK government said the cost of irrecoverable VAT for banks is hard to estimate, but it was probably about £4.5bn in 2017/18.

“The UK is not that uncompetitive in headline tax rates, but complexity is an issue. It’s not so much that the rate of tax is uncompetitive, but the complexity of rules can be a problem,” Stuttaford said.

What is clear is tax departments are hoping Truss and Kwarteng clarify changes soon. Major banks may have scores of staff in their tax teams, but the final quarter of the year is typically the busiest period and any changes from September onwards are always unwelcome.

Updated story: Adds comment from UK Finance paras 12-13