Heady equity valuations and a torrent of deal-making activity are helping deliver a record-busting year for corporate equity derivatives desks, a risky but lucrative corner of investment banks’ stock-trading units that helps investors and companies finance, hedge and manoeuvre in and out of large equity holdings.

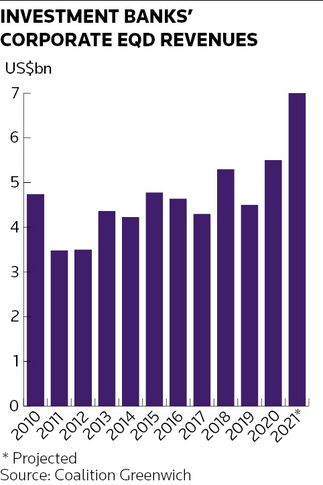

Global investment banks made US$3.5bn in revenues from corporate equity derivatives in the first half of the year, according to data analytics firm Coalition Greenwich, which projects an increase of roughly 25% in the annual revenue pool this year to a record high of about US$7bn.

That boom is providing a further lift to equities trading divisions at banks such as JP Morgan and Goldman Sachs that specialise in this area, while also fuelling competition among lenders including Barclays and BNP Paribas that are looking to grow these activities.

“This is a business that closely follows the banking cycle,” said Bregje de Best, co-head of global corporate derivatives at JP Morgan. "As it has been a very strong year for ECM and M&A, it’s not surprising to see a lot of activity in corporate equity derivatives too.”

Corporate equity derivatives encompass a broad set of activities focused on helping companies and investors increase or reduce exposure to chunky equity stakes, as well as borrowing money against these holdings. It sits apart from prime brokerage units where banks help hedge funds and other investors place and leverage trades, an area that came under scrutiny after more than US$10bn in industry losses from the collapse of Archegos Capital Management this year.

Much of the corporate equity derivatives business instead traces its origins to companies and investors hedging or financing large equity holdings following acquisitions or IPOs. That has evolved over the past two decades beyond the routine practice of banks lending against a company’s shares to incorporate a range of derivatives structures with varying degrees of complexity.

Big rewards, big risks

Transactions can be huge – and extremely profitable for banks. SoftBank Group Corp’s use of derivatives last year to raise money from two of its largest investments – Alibaba and T-Mobile US – provided hundreds of millions of US dollars in revenues to the small cluster of lenders that helped arrange those deals. The Japanese conglomerate has continued to be a prominent user of such trades this year (See box story).

Most corporate derivative transactions are agreed in private and so details rarely surface. But the size and concentration of these positions means losses can spiral quickly if deals sour.

In recent years, some lenders have looked to broaden their businesses and court a wider range of clients. “We’ve made a real effort to diversify our revenue streams and not be reliant on a couple of transactions each year,” said Steve Roti, global head of strategic equity solutions at Citigroup.

An infamous recent example of where it all went wrong came in 2017 when an accounting scandal at Steinhoff International inflicted more than US$1bn of losses across lenders including Bank of America, Citigroup, Goldman Sachs and JP Morgan stemming from margin loans to the South African retailer’s former chairman.

Deal deluge

Banks have different strategies to tap into client demand that usually hinge on connecting investment banking teams (who hold strong client relationships) with trading desks specialised in packaging and selling derivatives products.

Swiss banks, for instance, often lean on their vast wealth management units to drum up business with ultra-high net worth clients. Others focus more on private-equity firms or corporate banking clients, while US banks leverage their strong equity capital markets franchises.

“Each bank positions its business differently depending on its risk appetite and its client reach. This will be a great year for the industry, but I think people will have succeeded in very different ways," said Roti.

This year’s deal-making bonanza has certainly provided a steady stream of derivatives activity, whether it’s investors looking to leverage positions after an IPO or PE firms hedging cross-border acquisitions.

ECM desks, which tend to be the main driver of corporate derivatives trades, are having their busiest year on record with almost US$1trn in issuance in the first nine months of the year, according to Refinitiv data. Global M&A has already surpassed the full-year record with US$4.4trn of deals. The run-up in global stock markets, combined with periodic bouts of volatility, has also encouraged investors to hedge and take some chips off the table.

"Whenever you have rising equity markets, it brings the entire menu of corporate equity derivatives to the table,” said Ayo Akinluyi, global head of corporate equity derivatives at Barclays. “As we go into the end of the year, you’ll see more people thinking about hedging and monetisation given where prices are, just as many thought about financing a year ago.”

Beefing up

A number of banks have looked to beef up their offerings over the past year or so as industry revenues have grown. Goldman has expanded its margin loan book, according to several sources familiar with the matter, including acquiring some sizable positions on payments group Visa from Citigroup last year.

Morgan Stanley has also looked to increase its presence in these markets. The bank was involved in one of the largest trades this year when it helped finance the acquisition of a 12.1% stake in BT Group by Patrick Drahi, the billionaire founder of French telecoms firm Altice, sources said. BNP Paribas – another bank that has invested in corporate equity derivatives – was involved in the Altice transaction too, sources said.

Elsewhere, Barclays’ ambitions in corporate derivatives have stepped up a gear since the arrival of Paul Leech, the bank’s co-head of equities, who joined in 2020 after helping to build this business at JP Morgan. Even Deutsche Bank has quietly kept a foothold in this space despite announcing a wholesale exit from equities trading in 2019.

“Corporate equity derivatives can be a very profitable business for banks, particularly those with strong ECM franchises and big margin loan books in addition to strong corporate relationships, [plus] the know-how and risk appetite on the non-linear derivatives” said Youssef Intabli, a research director at Coalition Greenwich.

Risk management is also crucial – as previous mishaps have shown all too clearly. Parceling out exposure between banks is standard practice in concentrated margin loans, as well as some derivatives-based trades too. JP Morgan’s de Best notes that most of the risk management is in the structuring of the deal when it comes to less liquid stocks or solutions.

After all, not every position can be off-loaded. “By the nature of the business, you can't sell down every piece of risk. Clients are particularly sensitive about where paper gets placed in the market – you have a duty to protect that,” said Barclays’ Akinluyi. “Hedging rules vary from trade to trade, but we have a general culture of trying to create some velocity where possible.”

SoftBank: corporate derivatives behemoth

SoftBank has become one of the biggest corporate payers of investment banking fees, splurging nearly US$400m across loans, bonds, equities and M&A in the first nine months of 2021 alone, according to Refinitiv data.

It’s perhaps not surprising then that the Japanese conglomerate is also one of the most prominent users of corporate equity derivatives, providing another enormous source of revenue to its banks.

Goldman Sachs and JP Morgan were among the banks that made hundreds of millions of dollars in revenues between them for arranging a series of deals that helped SoftBank raise US$13.7bn against its stake in Chinese internet giant Alibaba last year, while also reducing its holdings in T-Mobile US in a separate set of transactions.

SoftBank-linked activity has continued to provide opportunities in 2021. Last month, Deutsche Telekom and SoftBank announced a share swap deal that would allow the German telecoms outfit to increase its stake in T-Mobile US. SoftBank would also become Deutsche Telekom’s second largest private shareholder under the deal.

Earlier this year, SoftBank borrowed US$1.9bn against its Alibaba shares through a margin loan and raised a further US$3bn through so-called pre-paid forward contracts – a derivatives structure whereby it commits to selling Alibaba shares in the future.

SoftBank’s use of corporate derivatives has produced mixed results. Pre-paid forward contracts on Alibaba it entered into between late 2019 and May 2021 had yielded a derivative loss of ¥109.7bn (US$962m), SoftBank said in its latest results.

It also recorded a ¥53.8bn loss from an increase in the value of T-Mobile call options it had previously sold to Deutsche Telekom. But that was comfortably offset by a ¥197.8bn gain coming from the rise in value of a so-called contingent consideration, which gives SoftBank the right to buy 48.8m T-Mobile shares if certain conditions are met.

SoftBank did not respond to requests for comment.