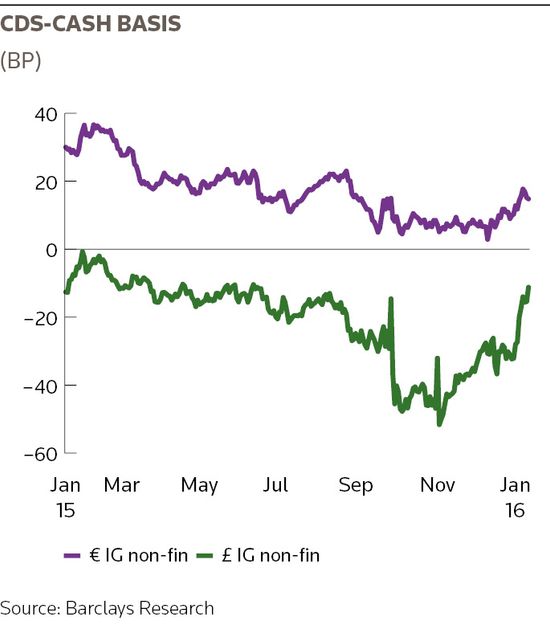

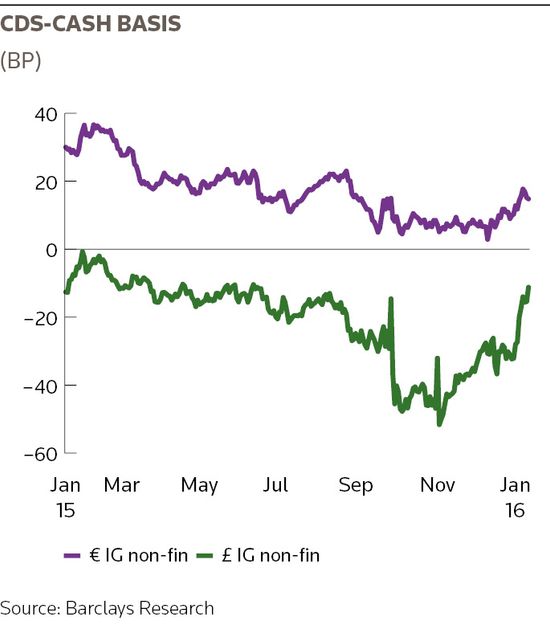

European basis reveals bond bias

| Updated:

You need to be a subscriber to view this content

All websites use cookies to improve your online experience. They were placed on your computer when you launched this website. You can change your cookie settings through your browser.