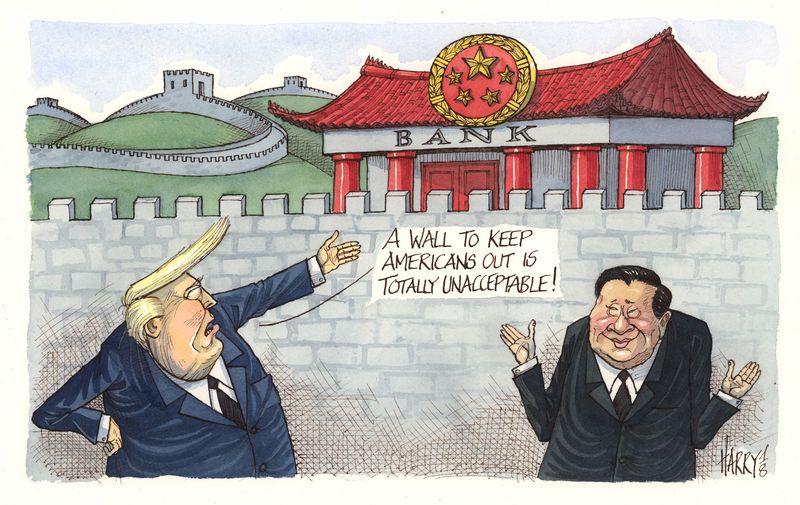

The barriers around China’s capital markets are coming down, just as politicians threaten to escalate Sino-US tensions into an all-out trade war.

![]()

China’s role in the global economy is under intense scrutiny, thanks in no small part to the US president’s Twitter account. But while Donald Trump continues to rail against unfair competition, intellectual property theft and currency manipulation, China’s financial markets are finally opening up.

“The theme of the opening up of China’s economy to the rest of the world has been talked about for decades, but the pace of change in the last 12 months has been remarkable,” said Julien Kasparian, head of securities services for Hong Kong at BNP Paribas.

“Whether you look on the equities side, where we had the inclusion of China A-shares in the MSCI index, or whether you look at fixed income, where China announced a number of changes to the market infrastructure following the launch of Bond Connect during the previous year, the pace of change has been quite staggering. And more importantly for foreign investors, access to China has never been so easy.”

Recent changes go beyond improving access for foreign investors. In April, China’s securities regulator finally gave the green light for foreign investment banks to hold majority stakes in their securities joint ventures and lifted similar restrictions on shareholdings for fund management and life insurance companies. Regulators have finalised a stock trading link between Shanghai and London and revived plans for overseas-listed companies to issue depositary receipts in China.

“The theme of the opening up of China’s economy to the rest of the world has been talked about for decades, but the pace of change in the last 12 months has been remarkable.”

“If you’re talking about the opening up of China’s financial sector, the real shift arguably began with the launch of the Stock Connect trading link between Shanghai and Hong Kong several years ago,” said Alexious Lee, head of China capital access at CLSA. “But whereas for the past several years the focus has been on testing the robustness of different access channels, we are now entering a different phase, which is about foreign investors stepping up their participation.”

The trillion-dollar question, of course, is whether tensions with the US will lead China to change course. Will regulators target US-based banks and asset managers in retaliation for trade tariffs? Or will the chilling effect on global growth force Chinese policymakers into a more protectionist stance to defend economic growth?

Most market observers are confident that China will continue to open its capital markets – gradually – even if tensions with the US escalate further.

“I think it’s partly due to the foreign reserves being under pressure so there is an incentive for the government to attract foreign investment,” said Caroline Yu, head of Greater China equities at BNP Paribas Asset Management.

The trillion-dollar question is whether tensions with the US will lead China to change course. Will regulators target US-based banks and asset managers in retaliation for trade tariffs? Or will the chilling effect on global growth force a more protectionist stance?

“But more importantly than that, China realises that increasing the participation of foreign institutional investors in its domestic capital markets is crucial to its long-term development. So I don’t expect them to shift position because of the trade tensions.”

INDEX ENDORSEMENT

There is plenty of US interest, too. The biggest endorsement of China’s reforms so far came from MSCI, which began adding A-shares to its benchmark emerging markets index this year. The New York-based index provider formally incorporated 226 large-cap mainland stocks with an initial weighting of 2.5% of market capitalisation in June before increasing their weighting to 5% in September.

MSCI has since outlined plans to increase the weighting of A-shares in its index to 20% of their market value in two phases next year. It has also said it plans to expand the universe of stocks available in its index to include shares listed on ChiNext, China’s equivalent of Nasdaq, as well as mid-cap A-shares, in a single phase next May.

Rival index provider FTSE Russell went a step further when it announced plans to add 1,250 A-shares, comprising large, mid and small cap stocks to its main indices in three phases from June 2019 to March 2020. Eligible stocks will have an initial weighting of 25% of market cap.

For Chin Ping Chia, head of research for Asia Pacific at MSCI, index inclusion highlights how quickly China is updating its regulatory framework to accommodate foreign institutional investors. Despite the escalation of international tensions, he sees that process as a one-way street.

“If you look at the rate of reforms since the launch of Stock Connect, it has been remarkable,” said Chia. “When the trade tensions first started there could have been concerns about whether China would back-pedal, but we actually have seen them accelerate some of the opening up measures. In April, they quadrupled the daily quota for the Connect schemes.”

Index providers have also welcomed investor-friendly reforms in the local market, including a proposal in November to curb the use of trading suspensions – a factor that drew international criticism when over 1,000 companies halted their shares in the midst of the 2015 crash.

“If you think about one of the big issues that remains, the number of share suspensions, one of the causes has been share pledges – to prevent margin calls the main shareholders have to suspend shares when the market slides – but we have actually seen regulators look to tighten a lot of the rules around voluntary suspensions this year,” said Chia. “This is during a year when the benchmark Shanghai index is down 20%.”

On the fixed income side, the lack of secondary market liquidity also remains an issue along with the lack of rating differentiation between credits, although plans to allow the big three global rating agencies – Fitch, Moody’s and S&P – to set up local operations will help address these issues.

Other reforms related to fixed income announced this year include the introduction of delivery versus payment settlement, the introduction of block trading and further clarity around taxation, effectively fulfilling the three prerequisites laid out earlier this year for inclusion in the Bloomberg Barclays Global Aggregate Index.

INVESTMENT BANKING

Efforts by Beijing to improve access for foreign institutional investors have gone hand-in-hand with reforms to lift restrictions on foreign banks operating onshore. In April, the China Securities Regulatory Commission introduced new rules allowing foreign banks to hold 51% stakes in their securities JVs, up from 49%, and also removed restrictions around obtaining licences.

Previously, foreign firms had to meet certain criteria, including a long operating track record, before applying for key licences. In many cases, regulations prohibiting JVs from holding the same licences as their domestic shareholders prevented them from applying for brokerage licences altogether.

Only HSBC, which invested under a specific deal between China, Hong Kong and Macau, currently holds a majority stake in a securities JV, but the changes to the rules have triggered a new wave of enthusiasm among international banks. UBS, which is one of only two banks to benefit from management control (Goldman Sachs is the other), is on the brink of becoming the first foreign bank to raise its stake to 51% after two of its partners, China Guodian Capital and Cofco Group, announced they had agreed to cut their shareholdings.

Morgan Stanley has also applied to increase its stake in its JV to 51%, while JP Morgan, which walked away from its partnership with First Capital Securities in 2016, has applied to set up a new JV. Citigroup is looking to exit from its partnership with Orient Securities to form a new JV with majority control, while a host of other banks, including DBS Group and Nomura, are lining up to enter the market for the first time.

China’s willingness to liberalise access for foreign investment banks initially took some commentators by surprise. The CSRC has even said it will remove the cap on foreign investment banks altogether within three years. Ray Chou, partner at Oliver Wyman, reckons this should be viewed in the context of efforts to increase the participation of foreign institutional investors in the domestic A-share market.

“One of the big changes that took place was in early 2017 when China changed the rules to allow foreign asset managers to launch private securities funds through local subsidiaries,” said Chou. “You now see there are 15-plus well-known global asset managers that have registered already as private fund managers.”

As well as the sheer size of China’s capital markets, Chou believes the growth of inbound investment is increasing the appeal of a domestic securities licence.

“There has been a concerted effort from the Chinese regulators to increase the participation of foreign institutional investors in the domestic capital markets. Meanwhile, foreign banks are well positioned to support global investors moving onshore and you will likely see increasing appetites among more foreign banks applying to set up JVs following the change in rules around ownership.”

Of course, for foreign investment banks looking to move onshore, the relaxation of rules around ownership and licences is only half the battle. Even on a level playing field, competing with domestic securities firms for lucrative secondary market business will be an uphill struggle given their superior scale and ingrained local connections.

CONNECT FOUR

Following on from the success of the Shanghai and Shenzhen Stock Connect trading links with Hong Kong (as well as Bond Connect), China has instituted a trading link with the UK, known as Shanghai-London Stock Connect. In contrast to the existing trading schemes with Hong Kong, investors will only be allowed to buy shares indirectly in the form of depositary receipts.

According to a draft consultation released in August, companies listed on the London Stock Exchange will be able to issue Chinese depositary receipts on the Shanghai Stock Exchange, while SSE-listed companies will issue global depositary receipts on the LSE. The major difference between the two is that LSE-listed companies can only issue CDRs backed by existing shares, at least for the time being, whereas Chinese companies are able to issue GDRs backed by new shares.

The new trading link has already attracted early interest, with Huatai Securities set to become the first to list GDRs under the scheme. In the other direction, the arrangement has allowed HSBC to dust off long-dormant plans for a domestic Chinese listing, potentially making it the first eastbound issuer.

A listing from Europe’s largest bank would also serve as a welcome boost for China after an experiment with CDRs earlier this year to attract more Chinese technology companies to float in their home market stuttered when smartphone maker Xiaomi postponed its planned CDR issuance. Market observers have even questioned whether this meant China had shelved its plans to encourage technology firms to list via CDRs indefinitely.

In contrast, market observers expect the development of the London trading link to be relatively smooth.

“The structure they have for Shanghai-London Connect is different than the previous Stock Connect schemes,” said Kasparian at BNP Paribas. “The fact that you have depositary receipts means that you avoid some of the issues around having different time zones, while there is already an established framework for clearing and settlement of DRs in London.”

STAKING A CLAIM

Despite the enthusiasm, there are still a lot of outstanding issues before China is able to claim its place in the global capital markets that the size of its economy warrants.

China’s capital markets may still lack some of the features global players would like, but the rewards at stake make them impossible to ignore. Even off its recent highs, the Chinese stock market still boasts a total valuation of over US$6.5trn and the Shenzhen bourse is the world’s most active by turnover, with trading especially busy on the technology-heavy US$600bn ChiNext board. Bond analysts estimate the reweighting of the major global indexes will add about US$280bn of foreign inflows to the country’s US$10trn domestic debt market.

CLSA’s Lee argues that international participants cannot afford to ignore reforms, even if progress at times appears slow.

“To take one example, ChiNext, which has had its issues and is going through the first cycle of restructuring, has still been phenomenally successful in my view. If you look at the increase in total turnover and trading volumes since it was launched, there is no comparison in other emerging economies,” he said.

“You should never underestimate what China is capable of doing.”

To see the digital version of this review, please click here .

To purchase printed copies or a PDF of this review, please email gloria.balbastro@tr.com .